The much misunderstood Premier

By Dr. Muhammad Reza Kazimi

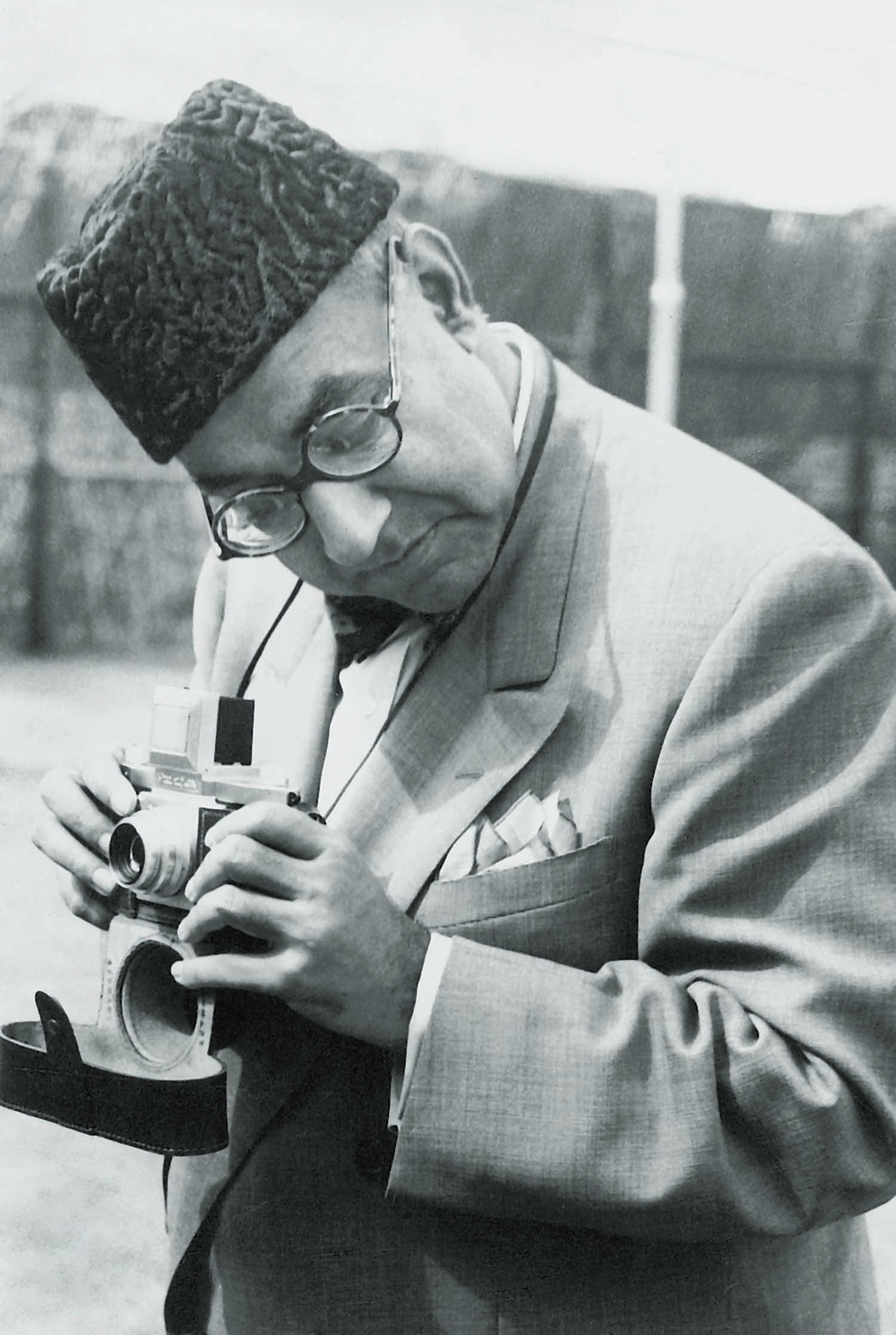

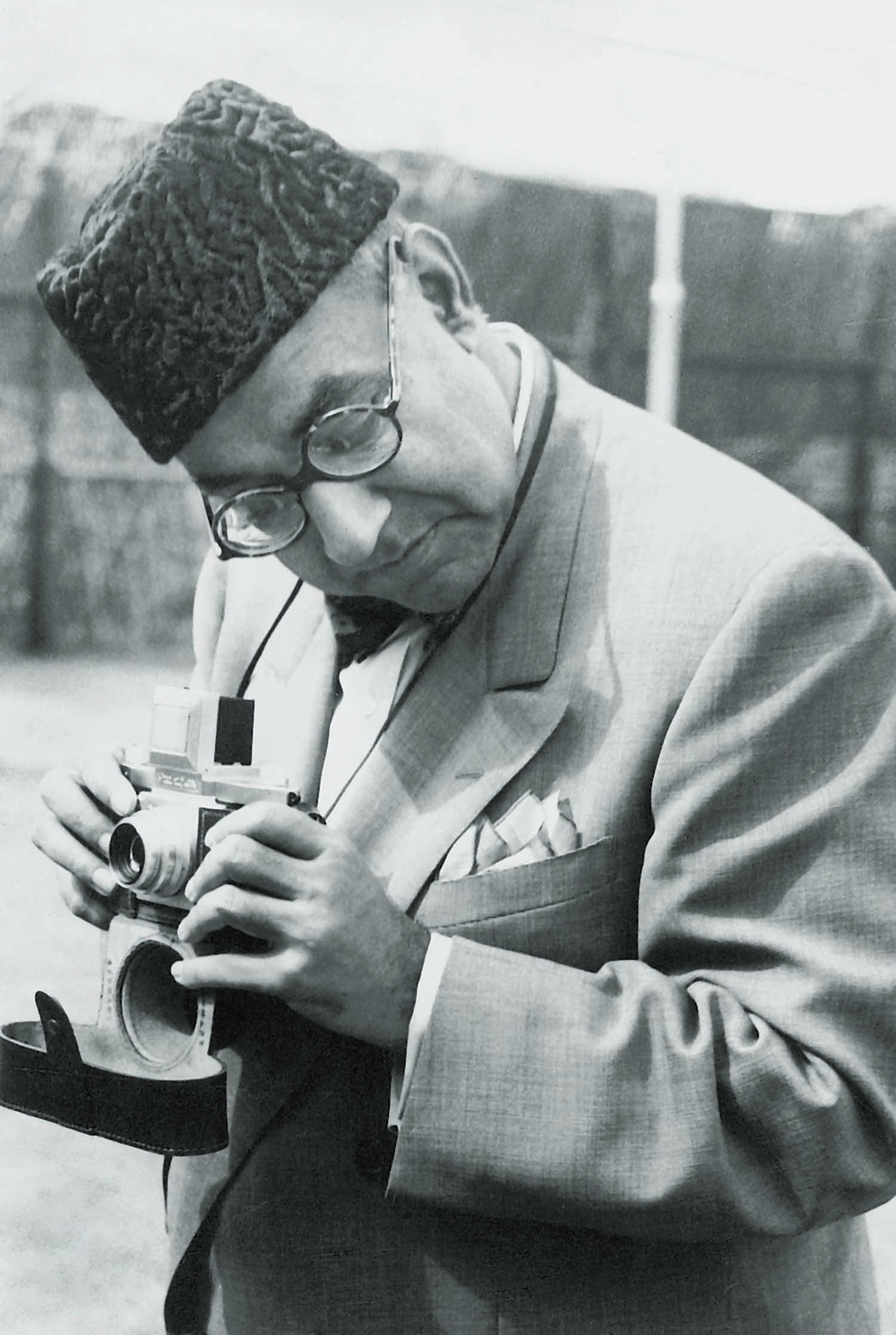

In addition to being an influential politician and everything else that he was, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan loved gadgets of all kinds and was an avid photographer. Here he is seen getting ready to take a snap of his beloved wife, Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan, during his state visit to the United States of America in May 1950. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

LIAQUAT Ali Khan was as pivotal to the consolidation of Pakistan as the Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, was central to the creation of Pakistan. He became the country’s first prime minister not simply because he was a trusted lieutenant of Jinnah, but by virtue of his proven leadership skills in having led the Muslim League bloc in the interim government before partition. Liaquat, having left all his property in India, refused to file a claim to which he was entitled as a ‘refugee’. The Nawabzada reduced his standard of life and set about building institutions in the new country. Such was the stuff the man was made of.

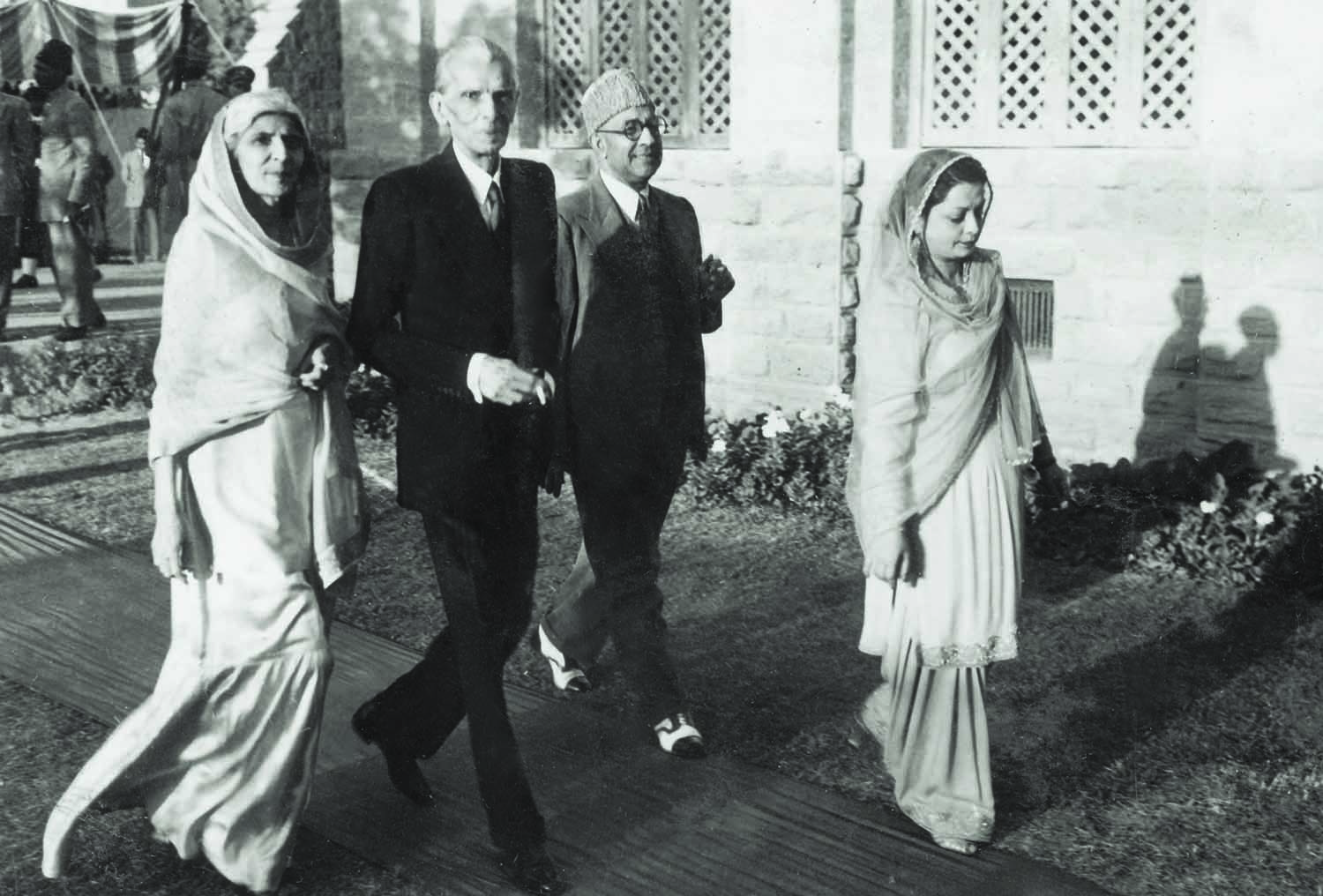

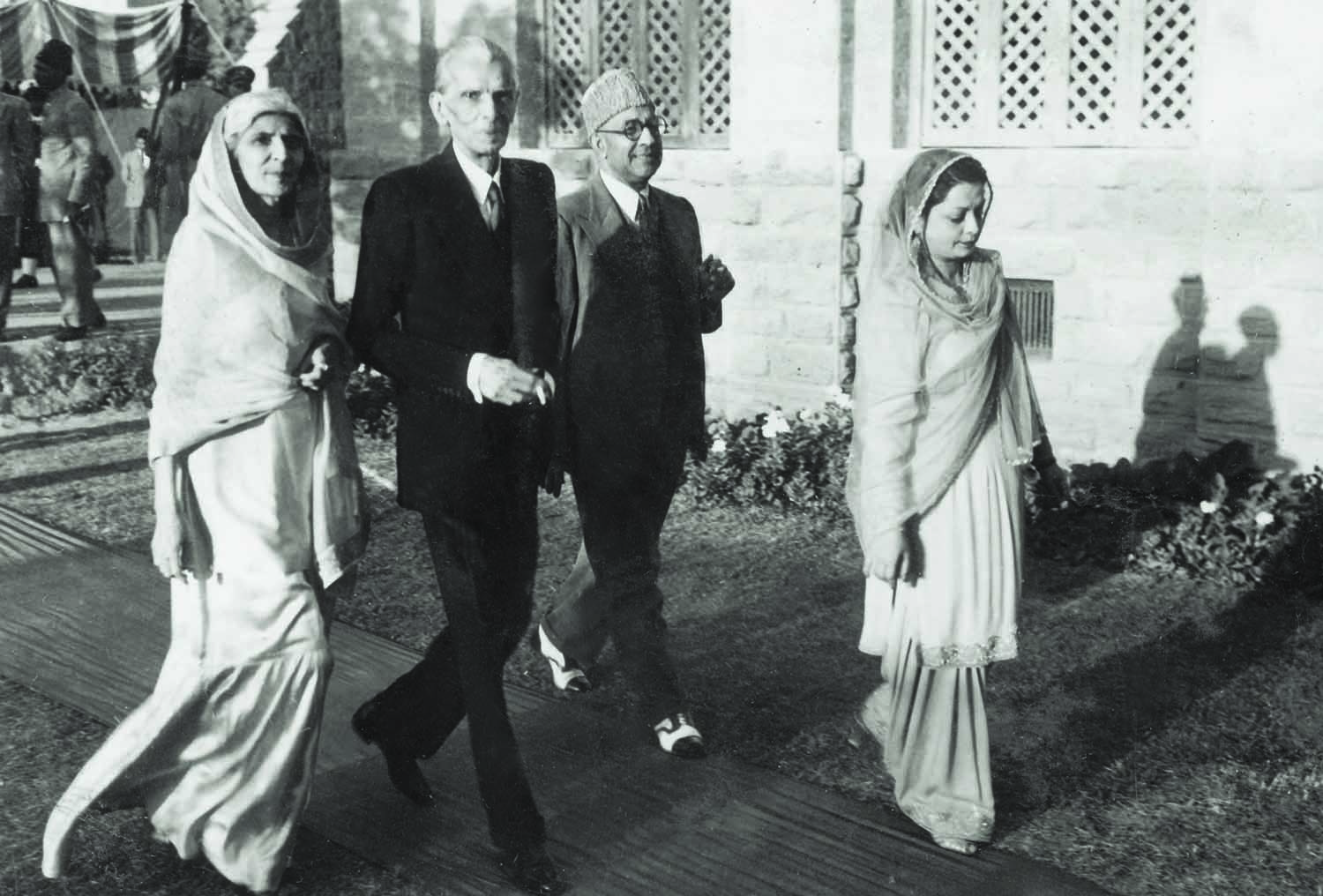

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Miss Fatima Jinnah (left) arriving in December 1946 at the Gul-e-Rana residence of Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan and Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan (right) in New Delhi to attend a reception given in honour of Mr Jinnah. | Photo: The Press Information Department, Ministry of Information, Broadcasting & National Heritage, Islamabad.

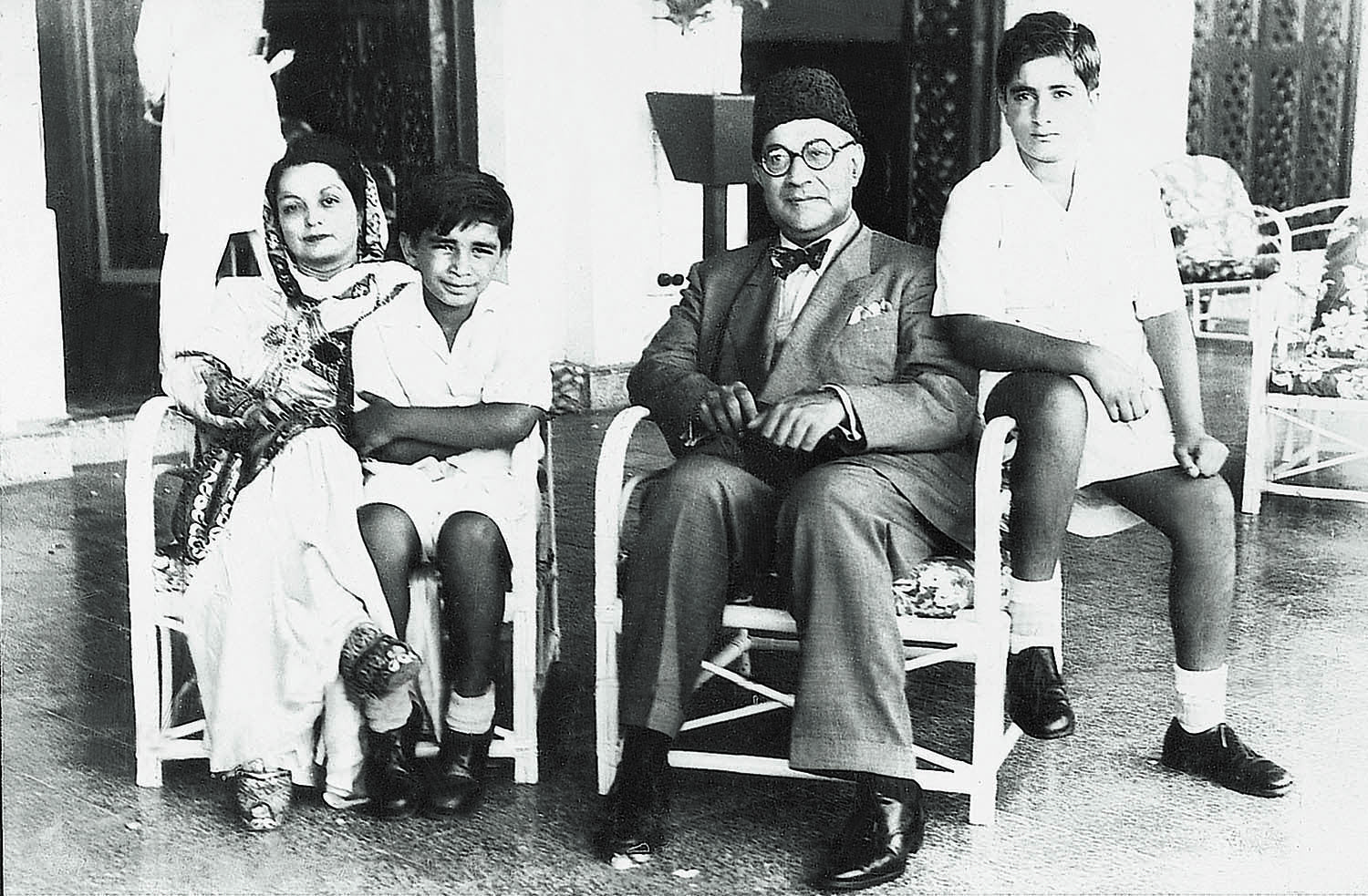

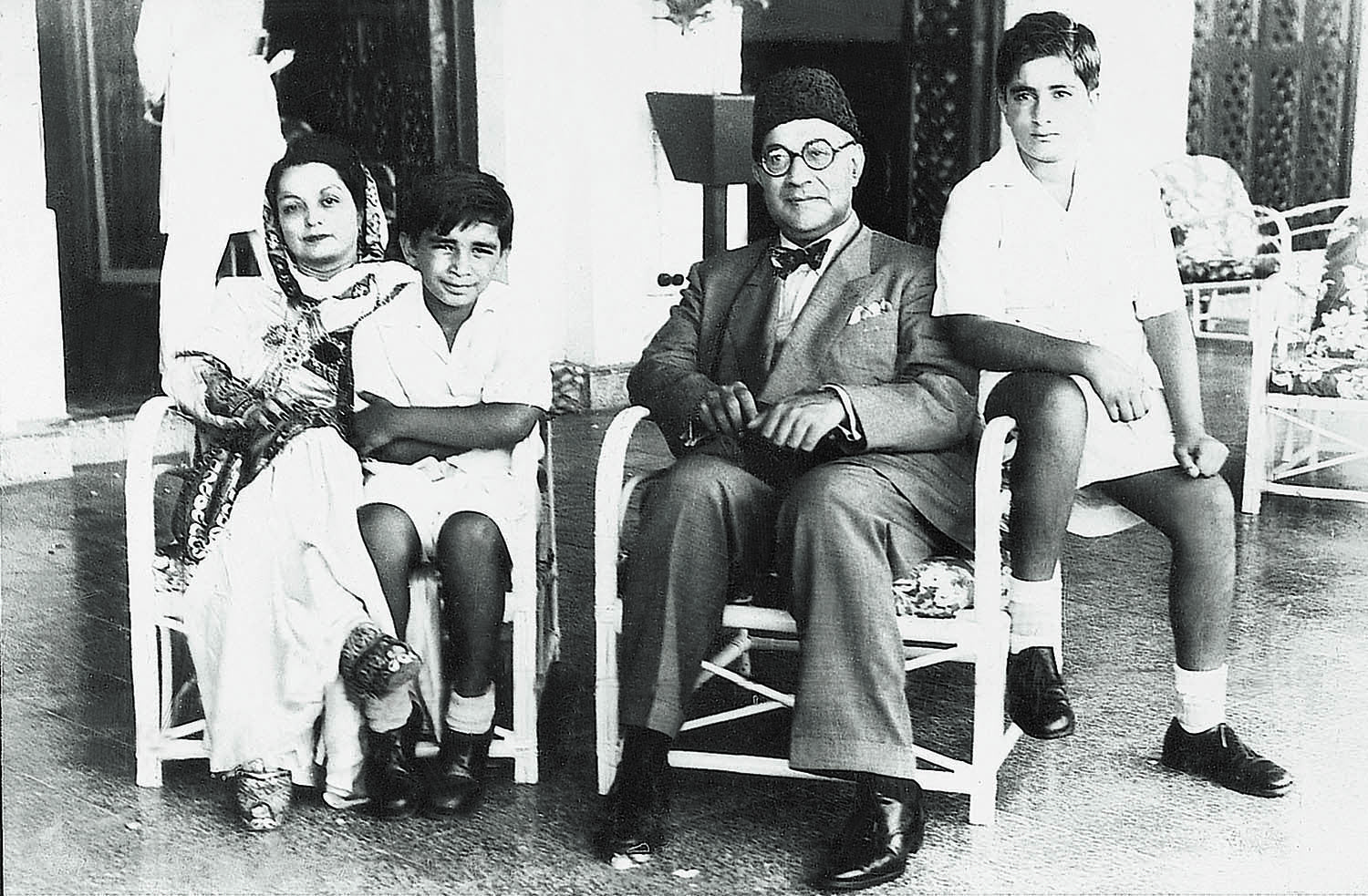

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan with Begum Rana Liaquat and their two sons Ashraf (left) and Akbar (right). | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The course of Pakistan’s journey can be seen meandering its way from a prime minister proverbial for his probity and down to his successors who every now and then faced investigations related to their wealth. It is no wonder, then, that after Pakistan had turned the corner in terms of consolidation, questions began to be raised regarding the constituency of Liaquat in Pakistan.

His tenure as prime minister is seen by certain quarters as having set a controversial path for the nation to follow. There have been two basic contentions. The first one relates to his decision to move away from what used to be the Soviet Union. The decision also had its reverberations in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy case.

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan signing his assent after having been sworn in as Pakistan’s first Prime Minister on August 15, 1947, in the presence of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah (right) on the grounds of the Governor General House in Karachi. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The first step in this direction was taken on May 3, 1948, when it was announced that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and Pakistan were to exchange ambassadors. On the occasion, Liaquat stated: “It has been the desire of Pakistan to have friendly relations with all the nations of the world, and the decision to exchange ambassadors with Russia is in consequence of that policy.”

The invitation for Liaquat to visit Moscow came a year later, on June 2, 1949, through the Soviet ambassador to Iran. Russia thereafter insisted that ambassadors be exchanged prior to Liaquat’s visit. Although on June 9, Sir Zafrullah Khan tried to stall the move, Liaquat proceeded regardless. The Pakistani ambassador was appointed on December 31, 1949, while the Soviet ambassador was appointed on March 22, 1950.

In June 1949, the USSR ‘advanced’ the date of the invitation, from August 20 to August 14. Liaquat could not agree to the date as it happened to be the first Independence Day of Pakistan after the Quaid-i-Azam’s demise. Subsequently came an invitation from the US and Liaquat proceeded there in May 1950.

Liaquat mentioned the Soviet invitation when leaving for the US, while he was on the US soil, and on his return home. A year later, Liaquat, while addressing a press conference in Karachi, explained the position thus: “I cannot go [to Moscow]until those people who invited me fix a date and ask me to go on such date … The invitation came. Later on, they suggested August 14, 1949. I replied that this is our Independence Day. I can come on any day after that; after that they have not replied”.

I am not the first to challenge the ‘myth’ of the Moscow invitation. Others, including Irtiza Husain, Mansur Alam and Shahid Amin, have preceded me. Syed Ashfaque Husain Naqvi, a diplomat based in Tehran at the time, rejected the allegation that Liaquat had cadged an invitation.

And this is what Dr. Samiullah Koreshi, who was posted at Moscow, related in his book ‘Diplomats and Diplomacy’: “Mr. Shuaib Qureshi was the first ambassador to USSR [in 1949] … He called on Andre Gromyko, then deputy foreign minister, to tell him that the prime minister had dispatched him post haste so that he could make all arrangements for his visit to Moscow in response to their invitation. [Gromyko replied] ‘Our invitation to your prime minister? Oh, you mean your proposal that he come here’.” Thereafter, the Soviet government did not revert to the subject.

The point is that the change of date having been made by the Soviets and Liaquat having conveyed his reservations clearly, Pakistan cannot be accused of having tried to pit one world power against the other, or of having picked up any of the two. He simply went ahead with the invitation that was valid and cannot be charged with failure to make use of the one that was not there on the table.

The other controversy regarding Liaquat’s tenure relates to the Objectives Resolution which is blamed for having opened the door for the subsequent Islamisation of General Ziaul Haq. Regardless of whether or not Pakistan was to be an Islamic state, the Pakistan movement clearly shows that it was not meant to be a territory with an ideology, but an ideology with a territory. Securing human rights and survival for a community suffering from religious discrimination is of ideological, and not of territorial, import.

The man that Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan was. No one ever doubted that the resolve behind the smile was ironclad. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The Objectives Resolution moved by Liaquat is denounced as a regressive document by which he allegedly sought to nullify the secular vision of the Quaid-i-Azam. To determine the veracity of the charge, we need to see three documents.

The first is the draft by the religious parties’ alliance. It read: “The Sovereignty of Pakistan belongs to Allah alone, and the Government of Pakistan has no right other than to enforce the will of Allah. The basic law of Pakistan is the Shariah of Islam. All those laws repugnant to Islam are to be revoked, and, in future, no such laws can be passed. The Government of Pakistan shall exercise its authority within the limits prescribed by Islamic Shariah.”

Now compare this draft with the one presented by Liaquat. It read: “Whereas the sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to Almighty Allah alone, and the authority which He has delegated to the State of Pakistan through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him is a sacred trust. This Constituent Assembly representing the people of Pakistan, resolves to frame a constitution of the sovereign independent state of Pakistan wherein the state shall exercise its power and authority through the chosen representatives of the people.”

What is the difference between the two drafts? The one presented by the ulema negates democracy, while Liaquat’s draft asserts it. Without democracy, even a minority sect can rule over a majority sect; a situation that has thrown the whole of the Middle East into confusion today.

The third document is the speech of Liaquat in the Constituent Assembly that he delivered on March 7, 1949, on the subject. “I assure the minorities that we are fully conscious of the fact that if the minorities are able to make a contribution to the sum total of human knowledge and thought, it will redound to the credit of Pakistan and will enrich the life of the nation. Therefore the minorities may look forward, not only to a period of the fullest freedom, but also to an understanding and appreciation on the part of the majority …

“Sir, there are a large number of interests for which the minorities desire protection. This protection this Resolution seeks to provide. We are fully conscious of the fact that they do not find themselves in their present plight for any fault of their own. It is also true that we are not responsible by any means for their present position. But now that they are our citizens, it will be our special effort to bring them up to the level of other citizens so that they may bear the responsibilities imposed by their being citizens of a free and progressive State ...”

It is true that members of the Pakistan National Congress had raised objections to the Resolution, but, among many others, it had the support of Sir Zafrullah Khan and Mian Ifthikharuddin who represented two divergent schools of thought and became part of religious and political minority in later years. And this in itself is a proof of Liaquat’s sincere intentions in moving the Objectives Resolution and of the tinkering that the Resolution suffered afterwards.

Besides, Liaquat had held out the assurance that the Objectives Resolution would not become a substantive part of the Constitution. This, and other linguistic jugglery, was done much later by General Ziaul Haq. Therefore, it is unjustifiable to blame Liaquat for the excesses caused by the dictator that opened the door for even more abuse than he himself probably thought of.

Whatever the critics might say, Liaquat was what he was. It was a real achievement on his part that he could set Pakistan on the course to industrialisation. Western countries, seeking to ensure Pakistan’s demise, refused to supply even on payment, machinery and parts. They wanted Pakistan to be subservient to India. Liaquat nevertheless was able to procure the necessary equipment from East European countries in return for hard cash.

Sishir Chandra Chattopadhaya had stated on the floor of the Constituent Assembly that the link between East Bengal and Calcutta could not be broken. Liaquat broke the link.He refused to devalue currency when Britain and India did so. In the face of the Indian threat not to lift jute at the new price, Liaquat went to the growers, directly pleading with them not to sell at the old rate. If need be, the government of Pakistan would lift the entire stock, he assured the growers. The jute mills of Calcutta could not run without jute from East Bengal and, ultimately, the owners purchased at the new rate. This single decision enabled Liaquat to derive full benefit from the boom created by the Korean War, and the country, which had been written off as unviable, became more than solvent.

The British, since 1857, had imposed certain standards for the recruitment of soldiers. Liaquat removed them and started the induction of Bengalis in Pakistan Army. Similarly, there was only one ICS officer from East Pakistan, Nurun-Nabi Choudhry. Liaquat immediately fixed a 50 per cent quota for East Bengal civil servants to generate parity.

Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan (extreme right) sitting in mourning as the body of the slain Prime Minister, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, lay in state before the burial. He was assassinated on October 16, 1951, during a public rally at Rawalpindi’s Company Bagh which was later renamed Liaquat Bagh. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The critics of Liaquat survived, but Liaquat did not. And he died in circumstances that have never allowed anyone to pinpoint the actual killer … or killers. Liaquat’s life and actions generated controversies when there should have been none, and his death remains a controversy that failed to generate much interest where it mattered. Liaquat definitely deserved better.

source :

By Dr. Muhammad Reza Kazimi

In addition to being an influential politician and everything else that he was, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan loved gadgets of all kinds and was an avid photographer. Here he is seen getting ready to take a snap of his beloved wife, Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan, during his state visit to the United States of America in May 1950. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

LIAQUAT Ali Khan was as pivotal to the consolidation of Pakistan as the Quaid-i-Azam, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, was central to the creation of Pakistan. He became the country’s first prime minister not simply because he was a trusted lieutenant of Jinnah, but by virtue of his proven leadership skills in having led the Muslim League bloc in the interim government before partition. Liaquat, having left all his property in India, refused to file a claim to which he was entitled as a ‘refugee’. The Nawabzada reduced his standard of life and set about building institutions in the new country. Such was the stuff the man was made of.

Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Miss Fatima Jinnah (left) arriving in December 1946 at the Gul-e-Rana residence of Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan and Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan (right) in New Delhi to attend a reception given in honour of Mr Jinnah. | Photo: The Press Information Department, Ministry of Information, Broadcasting & National Heritage, Islamabad.

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan with Begum Rana Liaquat and their two sons Ashraf (left) and Akbar (right). | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The course of Pakistan’s journey can be seen meandering its way from a prime minister proverbial for his probity and down to his successors who every now and then faced investigations related to their wealth. It is no wonder, then, that after Pakistan had turned the corner in terms of consolidation, questions began to be raised regarding the constituency of Liaquat in Pakistan.

His tenure as prime minister is seen by certain quarters as having set a controversial path for the nation to follow. There have been two basic contentions. The first one relates to his decision to move away from what used to be the Soviet Union. The decision also had its reverberations in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy case.

Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan signing his assent after having been sworn in as Pakistan’s first Prime Minister on August 15, 1947, in the presence of Quaid-i-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah (right) on the grounds of the Governor General House in Karachi. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The first step in this direction was taken on May 3, 1948, when it was announced that the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) and Pakistan were to exchange ambassadors. On the occasion, Liaquat stated: “It has been the desire of Pakistan to have friendly relations with all the nations of the world, and the decision to exchange ambassadors with Russia is in consequence of that policy.”

The invitation for Liaquat to visit Moscow came a year later, on June 2, 1949, through the Soviet ambassador to Iran. Russia thereafter insisted that ambassadors be exchanged prior to Liaquat’s visit. Although on June 9, Sir Zafrullah Khan tried to stall the move, Liaquat proceeded regardless. The Pakistani ambassador was appointed on December 31, 1949, while the Soviet ambassador was appointed on March 22, 1950.

In June 1949, the USSR ‘advanced’ the date of the invitation, from August 20 to August 14. Liaquat could not agree to the date as it happened to be the first Independence Day of Pakistan after the Quaid-i-Azam’s demise. Subsequently came an invitation from the US and Liaquat proceeded there in May 1950.

Liaquat mentioned the Soviet invitation when leaving for the US, while he was on the US soil, and on his return home. A year later, Liaquat, while addressing a press conference in Karachi, explained the position thus: “I cannot go [to Moscow]until those people who invited me fix a date and ask me to go on such date … The invitation came. Later on, they suggested August 14, 1949. I replied that this is our Independence Day. I can come on any day after that; after that they have not replied”.

I am not the first to challenge the ‘myth’ of the Moscow invitation. Others, including Irtiza Husain, Mansur Alam and Shahid Amin, have preceded me. Syed Ashfaque Husain Naqvi, a diplomat based in Tehran at the time, rejected the allegation that Liaquat had cadged an invitation.

And this is what Dr. Samiullah Koreshi, who was posted at Moscow, related in his book ‘Diplomats and Diplomacy’: “Mr. Shuaib Qureshi was the first ambassador to USSR [in 1949] … He called on Andre Gromyko, then deputy foreign minister, to tell him that the prime minister had dispatched him post haste so that he could make all arrangements for his visit to Moscow in response to their invitation. [Gromyko replied] ‘Our invitation to your prime minister? Oh, you mean your proposal that he come here’.” Thereafter, the Soviet government did not revert to the subject.

The point is that the change of date having been made by the Soviets and Liaquat having conveyed his reservations clearly, Pakistan cannot be accused of having tried to pit one world power against the other, or of having picked up any of the two. He simply went ahead with the invitation that was valid and cannot be charged with failure to make use of the one that was not there on the table.

The other controversy regarding Liaquat’s tenure relates to the Objectives Resolution which is blamed for having opened the door for the subsequent Islamisation of General Ziaul Haq. Regardless of whether or not Pakistan was to be an Islamic state, the Pakistan movement clearly shows that it was not meant to be a territory with an ideology, but an ideology with a territory. Securing human rights and survival for a community suffering from religious discrimination is of ideological, and not of territorial, import.

The man that Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan was. No one ever doubted that the resolve behind the smile was ironclad. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The Objectives Resolution moved by Liaquat is denounced as a regressive document by which he allegedly sought to nullify the secular vision of the Quaid-i-Azam. To determine the veracity of the charge, we need to see three documents.

The first is the draft by the religious parties’ alliance. It read: “The Sovereignty of Pakistan belongs to Allah alone, and the Government of Pakistan has no right other than to enforce the will of Allah. The basic law of Pakistan is the Shariah of Islam. All those laws repugnant to Islam are to be revoked, and, in future, no such laws can be passed. The Government of Pakistan shall exercise its authority within the limits prescribed by Islamic Shariah.”

Now compare this draft with the one presented by Liaquat. It read: “Whereas the sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to Almighty Allah alone, and the authority which He has delegated to the State of Pakistan through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him is a sacred trust. This Constituent Assembly representing the people of Pakistan, resolves to frame a constitution of the sovereign independent state of Pakistan wherein the state shall exercise its power and authority through the chosen representatives of the people.”

What is the difference between the two drafts? The one presented by the ulema negates democracy, while Liaquat’s draft asserts it. Without democracy, even a minority sect can rule over a majority sect; a situation that has thrown the whole of the Middle East into confusion today.

The third document is the speech of Liaquat in the Constituent Assembly that he delivered on March 7, 1949, on the subject. “I assure the minorities that we are fully conscious of the fact that if the minorities are able to make a contribution to the sum total of human knowledge and thought, it will redound to the credit of Pakistan and will enrich the life of the nation. Therefore the minorities may look forward, not only to a period of the fullest freedom, but also to an understanding and appreciation on the part of the majority …

“Sir, there are a large number of interests for which the minorities desire protection. This protection this Resolution seeks to provide. We are fully conscious of the fact that they do not find themselves in their present plight for any fault of their own. It is also true that we are not responsible by any means for their present position. But now that they are our citizens, it will be our special effort to bring them up to the level of other citizens so that they may bear the responsibilities imposed by their being citizens of a free and progressive State ...”

It is true that members of the Pakistan National Congress had raised objections to the Resolution, but, among many others, it had the support of Sir Zafrullah Khan and Mian Ifthikharuddin who represented two divergent schools of thought and became part of religious and political minority in later years. And this in itself is a proof of Liaquat’s sincere intentions in moving the Objectives Resolution and of the tinkering that the Resolution suffered afterwards.

Besides, Liaquat had held out the assurance that the Objectives Resolution would not become a substantive part of the Constitution. This, and other linguistic jugglery, was done much later by General Ziaul Haq. Therefore, it is unjustifiable to blame Liaquat for the excesses caused by the dictator that opened the door for even more abuse than he himself probably thought of.

Whatever the critics might say, Liaquat was what he was. It was a real achievement on his part that he could set Pakistan on the course to industrialisation. Western countries, seeking to ensure Pakistan’s demise, refused to supply even on payment, machinery and parts. They wanted Pakistan to be subservient to India. Liaquat nevertheless was able to procure the necessary equipment from East European countries in return for hard cash.

Sishir Chandra Chattopadhaya had stated on the floor of the Constituent Assembly that the link between East Bengal and Calcutta could not be broken. Liaquat broke the link.He refused to devalue currency when Britain and India did so. In the face of the Indian threat not to lift jute at the new price, Liaquat went to the growers, directly pleading with them not to sell at the old rate. If need be, the government of Pakistan would lift the entire stock, he assured the growers. The jute mills of Calcutta could not run without jute from East Bengal and, ultimately, the owners purchased at the new rate. This single decision enabled Liaquat to derive full benefit from the boom created by the Korean War, and the country, which had been written off as unviable, became more than solvent.

The British, since 1857, had imposed certain standards for the recruitment of soldiers. Liaquat removed them and started the induction of Bengalis in Pakistan Army. Similarly, there was only one ICS officer from East Pakistan, Nurun-Nabi Choudhry. Liaquat immediately fixed a 50 per cent quota for East Bengal civil servants to generate parity.

Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan (extreme right) sitting in mourning as the body of the slain Prime Minister, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, lay in state before the burial. He was assassinated on October 16, 1951, during a public rally at Rawalpindi’s Company Bagh which was later renamed Liaquat Bagh. | Photo: Dawn / White Star Archives

The critics of Liaquat survived, but Liaquat did not. And he died in circumstances that have never allowed anyone to pinpoint the actual killer … or killers. Liaquat’s life and actions generated controversies when there should have been none, and his death remains a controversy that failed to generate much interest where it mattered. Liaquat definitely deserved better.

source :