Highlights

- The world's leading powers will continue to attract the offspring of the developing world's ruling elites to their educational institutions.

- In so doing, host countries hope that the ostensible bonds they form with elites from abroad will provide an opportunity to exert influence in the years to come.

- As some countries in the Western world seek to reduce immigration, countries like China will draw more international students.

At Stratfor, we aim to provide impartial geopolitical analysis and forecasts. More often than not, this means withholding our emotions as we focus on the underlying compulsions and constraints with which global actors must grapple. In a sense, the individual performs a reduced role in the much larger game playing out on the world stage. In some affairs of state, however, individuals can drive policy. In such situations, outcomes might depend heavily on individuals' emotional decisions, particularly when driven by short-term interests. And given that people are emotional creatures who develop affinities and aversions based on their formative years, many powerful governments place great emphasis on ensuring that the ruling elites of other countries receive an education in their countries, fighting silent battles to entice them as part of a far-sighted competition for influence.

How to Win Friends and Influence People

It should come as no surprise that states constantly search for ways to boost their clout. One tried-and-tested method that countries have used for generations is to open their doors to the family members of ruling elites in developing countries. The policy has two upsides. First, it provides a favor to the powers that be in a given country by graciously hosting their family – and, frequently, their security details – while offering the former with a top-notch education. Second, it may potentially put the host country in line for a payoff years later should that favored son or daughter eventually rise to a position of power.

What defines many people is not their place of birth but where they came of age. Because university education occurs at around the impressionable age of 18, the place where a person receives that education can have an outsized influence on his or her outlook on the world. Accordingly, top schools around the world actively recruit elite international students (their hard cash naturally helps sweeten the deal) to attend their universities, rub shoulders with their citizens and develop a taste for their culture. For example, on his first day in the United States, Saudi Prince Bandar bin Sultan (who went on to study at Johns Hopkins University and later served as the Saudi ambassador to Washington from 1983 to 2005) became entranced by the Dallas Cowboys' cheerleading squad, who he saw at an airport terminal. The moment made him a fan of the football team for life, and even led him to purchase a $500,000-a-year private box at the team's stadium. While impossible to quantify, little moments like this can provide points of reference and forge lasting and productive bonds between government interlocutors.

European states that once had expansive global empires like the United Kingdom and France have played this influence game for a long time. The doors to venerable institutions like Oxford and Cambridge, Sciences Po Paris or the Sandhurst and Saint Cyr military academies remain open to the children of ruling families in their former colonial spaces in Africa, the Middle East and elsewhere. The list of family members from Gulf monarchies who have attended Royal Military Academy Sandhurst is extensive, providing a lasting link between London and these energy-rich countries long after their formal colonial ties faded into history.

France has aggressively sought to maintain its influence in Africa and elsewhere as part of its state strategy. Paris has accomplished its goals in part by supporting the Alliance Francaise, the global network of schools that have propagated French language and culture since 1883, and accepting untold numbers of future Francophone leaders at its universities and military academies. Cold War-era African leaders like the late president of Ivory Coast, Felix Houphouet-Boigny, were such ardent francophiles that the longtime Ivorian chief of state had a tunnel built between his presidential residence and the French Embassy for easy and discreet access. In fact, France has been so successful at capturing the hearts and minds of Francophone elites over the decades that the country's foreign policymakers have changed tack under President Emmanuel Macron to focus more on winning support from the "real" population as opposed to merely cultivating elites. Macron's administration has also underscored the need to escape the boundaries of Africa's Francophone world and chart a course for other parts of the continent. Sciences Po Paris' recent decision to open a recruitment center in decidedly Anglophone Nairobi – France's first such hub outside its former colonial backyard – is testament to this new push.

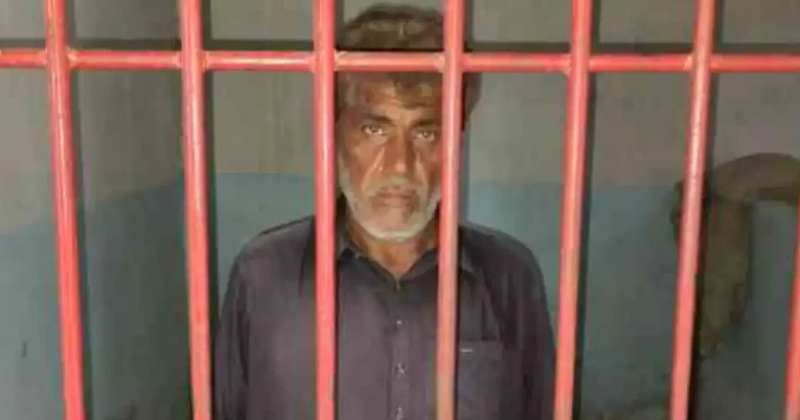

Crown Prince Hussein bin Abdullah (center) stands at ease during the Commissioning Parade at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, Aug. 11, 2017. His father, King Abdullah II of Jordan, also a Sandhurst graduate, was the reviewing officer.

While elite French and British institutions of higher educational maintain their cachet, U.S. institutions have risen in popularity for elites over the decades to match its status as the global superpower, frequently attracting students from former British colonies. Some, like Jordan's King Abdullah II, opted for a hybrid education that gave him a foot in the two Western countries that back Jordan most. Before he became king, Abdullah attended British prep schools, the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and Oxford before heading across the Atlantic for more education at Georgetown University and the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. Still, the United Kingdom does sometimes get the better of its former colony in the race to secure the interest of another son of a prominent person. According to Steve Coll's Directorate S: The C.I.A. and America's Secret Wars in Afghanistan and Pakistan, U.S. intelligence admitted to making two mistakes with regard to Ahmad Massoud and his father, Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Afghan military leader. First, the United States failed to listen to warnings from the elder Massoud about the dangers of al Qaeda prior to Sept. 11, 2001, (he would die at the group's hands just two days before 9/11), and second, it lost out to the British in terms of providing an education for the younger Massoud, who opted for Sandhurst and the London School of Economics instead of West Point and a U.S. university.

Less influential were the efforts by the Soviet Union during the Cold War to shape the minds of international students. The People's Friendship University of Russia, once known as Patrice Lumumba University after the slain Congolese independence leader, hosted dozens of future leaders of the developing world during the Cold War. This provided the Soviet Union with an opportunity to forge prospective leaders of the socialist revolution such as the international terrorist Carlos the Jackal, Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega and Timoleon Jimenez, better known as Timochenko, the leader of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). But the end of the Cold War deprived Russia of its paramount importance – and the need to mold new socialist leaders. After 1991, global elites, regardless of their ideological proclivities, also shifted to sending their children to U.S. and Western European universities to take advantage of the quality education and prestige. Indeed, according to some unconfirmed reports, even North Korean elites have sent their children to U.S. schools under assumed names and citizenships.

In recent years, more countries have opened their doors to an ever greater number of international students, not just the children of rulers. More foreign students are studying in the United States, France, the United Kingdom, China, South Korea and elsewhere than ever before. But student visa restrictions stemming from restrictions on immigration in the former colonial metropoles of the United Kingdom and France, as well as the United States, have opened the door for other countries. For example, the number of African students studying in China alone over the past 15 years has increased 26 times, growing from a couple thousand at the turn of the millennium to more than 50,000 today. This and the growing number of Confucius Centers around the globe represent a broader soft power effort by Beijing than just the children of a country's ruler. And China isn't alone: Turkey has had success in opening schools in other countries (at least until the rupture between the Gulen movement, which spearheaded the institutions, and the government). Those schools gave thousands of students the chance to learn Turkish and other languages.

How Not to Win Friends and Influence People

But while governments may assume that the next generation of foreign leaders attending their schools may foster a certain degree of affinity for the host nation, that is not always the case. More than half a dozen Iranian leaders in President Hassan Rouhani's administration attended U.S. universities and elsewhere in the West before and after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, but such educational links did not institute much fondness for Washington and its allies. In fact, one could argue that the Western-educated Iranian leadership's intimate understanding of their one-time hosts has even lent them an advantage in pursuing Tehran's foreign policy objectives. Likewise for one Saloth Sar, an education in Paris at the turn of the 1950s engendered little appreciation in him for France's foreign policy aims in Indochina. Sar later returned home, helped fight the French and eventually took over his native land of Cambodia – by which time he had adopted the nom de guerre the world would know him by: Pol Pot.

On the other end of the scale, elite students who pull the wool over their hosts' eyes can also create headaches for the latter's governments in the long run. One particularly notorious example was Ahmed Chalabi, an Iraqi politician and founder of the opposition Iraqi National Congress. Chalabi studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he would perfect an American accent and mannerisms, qualities that would endear him to the George W. Bush administration despite his questionable credentials as a leader of national prominence in the run-up to the Iraq War.

Harvard for Me, National Pride for You

As with any parent, there is enormous pride when a leader's child attends a prestigious university. For the university, this is generally a win-win as it can further boost the institution's prestige and result in lucrative donations from a grateful graduate down the road. But by sending their children off to distant, elite institutions abroad, ruling classes sometimes drive home an uncomfortable truth: The educational systems in their own countries are subpar. Just like when wealthy and influential people travel abroad for medical procedures, a foreign education for a favored son or daughter can attract the ire of nationalists. Perhaps this is what makes Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's lack of foreign education all the more remarkable. He eschewed the chance to pursue a prestigious degree at Harvard University or similar U.S. institution in favor or earning a bachelor's degree at King Saud University. What's more, records indicate that the crown prince also did not pursue study abroad programs, meaning that he, unlike previous Saudi leaders, lacked the cultural experience and alumni relationships that are part and parcel of exchange programs and which Saudi leaders have enjoyed for decades.

Beyond a world in which military might provides power, a far more subtle battle for influence rages on among the leaders of the Western world, as well as the ambitious newcomers to power politics in the 21st century. Together, countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, France and China are striving to attract the children who will become tomorrow's ruling elite throughout the developing world. In providing an education to elites from elsewhere, host countries might not guarantee themselves preferential treatment from their former students down the road, but the chance that an overseas education will endear a global power to a future leader is too hard to pass up. From North America to Europe and the Far East, it's an outlay that countries are willing to make in the hopes of a later payoff.

https://worldview.stratfor.com/arti...ation-unconventional-tool-political-influence