RiazHaq

Senator (1k+ posts)

General Suharto stepped down about 15 years ago. Here's an excerpt of today's New York Times story on the Indonesian strongman's legacy:

"Mr. Suhartos spirit continues to loom over modern-day Indonesia. He brought the country back from the brink of political, social and economic calamity in the mid-1960s,dramatically reduced poverty and by the early 1990s had turned Indonesia into one of the Asian tiger economies. But he also governed with an iron fist, sending his jackbooted military into separatist-minded regions, jailing and exiling political enemies, quashing democratic institutions and the news media, and presiding over what some claim is one of the most corrupt governments in modern history.....Tuesday is the 15th anniversary of Mr. Suhartos resignation as president. .... Since then, Indonesia has undergone a dramatic transformation toward democracy and now has open elections and the worlds 16th-largest economy. Yet corruption remains endemic, crime is higher than during Mr. Suhartos New Order regime, and Jakarta and other large cities have chronic traffic problems".

Both Indonesia and Pakistan have each seen about 30 years of military rule. So why has Indonesia become an Asian tiger economy and Pakistan has not?

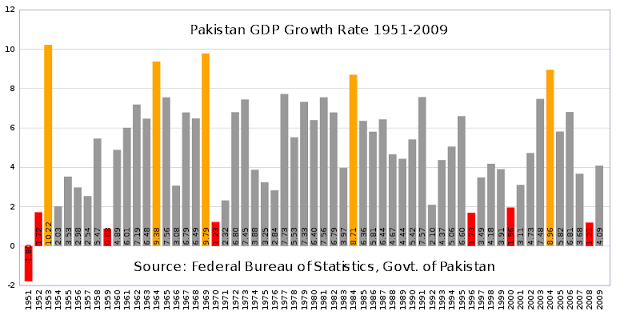

One possible explanation is that while there was 32 years uninterrupted military rule with sustained development in Indonesia, Pakistan has seen three stints of high growth under military generals in 1960s, 1980s and 2000s separated by three periods of slow or very slow growth under civilian rule in 1950s, 1970s and 1990s. Pakistani military rulers have also been less ruthless and more benevolent than Gen Suharto.

Pakistan has also experienced economic andsocial progress comparable to Indonesia's during periods of military rule. There has been much better governance and significantly faster rates of economic and social development during military rule than under civilian leaders. Many economists persuasively argue that Pakistan would have developed as fast as South Korea had the Ayub era policies continued uninterrupted for another decade or two.

Pakistan's first military dictator General Ayub Khan's period is labeled by Pakistani economist Dr. Ishrat Husain as "the Golden Sixties". General Ayub Khan pushed central planning with a state-driven national industrial policy. Countries like Malaysia and South Korea saw Pakistan as a model for export-led growth, according to Prof Stephen Cohen. In fact, South Korea sought to emulate Pakistan's development strategy and copied Pakistan's second "Five-Year Plan".

Here's how Dr. Husain recalls Pakistan of 1960s:

"The manufacturing sector expanded by 9 percent annually and various new industries were set up. Agriculture grew at a respectable rate of 4 percent with the introduction of Green Revolution technology. Governance improved with a major expansion in the governments capacity for policy analysis, design and implementation, as well as the far-reaching process of institution building. The Pakistani polity evolved from what political scientists called a soft state to a developmental one that had acquired the semblance of political legitimacy. By 1969, Pakistans manufactured exports were higher than the exports of Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia combined. Though speculative, it is possible that, had the economic policies and programs of the Ayub regime continued over the next two decades, Pakistan would have emerged as another miracle economy."

Pakistanis have found that each time a military ruler has been forced out and replaced by a civilian government led by politicians, both the economic and the social indicators have suffered. For example, Pakistan's decade of 1990s under the PPP and the PML rule is remember by economists as the lost decade. It was followed by a rebound of robust social and economic development during the Musharraf period from year 2000 to 2007.

In the 1990s, economic growth plummeted to between 3% and 4%, poverty rose to 33%, inflation was in double digits and the foreign debt mounted to nearly the entire GDP of Pakistan as the governments of Benazir Bhutto (PPP) and Nawaz Sharif (PML) played musical chairs. Before Sharif was ousted in 1999, the two parties had presided over a decade of corruption and mismanagement. In 1999 Pakistans total public debt as percentage of GDP was the highest in South Asia 99.3 percent of its GDP and 629 percent of its revenue receipts, compared to Sri Lanka (91.1% & 528.3% respectively in 1998) and India (47.2% & 384.9% respectively in 1998). Internal Debt of Pakistan in 1999 was 45.6 per cent of GDP and 289.1 per cent of its revenue receipts, as compared to Sri Lanka (45.7% & 264.8% respectively in 1998) and India (44.0% & 358.4% respectively in 1998).

The year 1999 brought a bloodless coup led by General Pervez Musharraf, ushering in an era of accelerated economic growth that led to more than doubling of the national GDP, and dramatic expansion in Pakistan's urban middle class. Pakistan became one of the four fastest growing economies in the Asian region during 2000-07 with its growth averaging 7.0 per cent per year for most of this period. As a result of strong economic growth, Pakistan succeeded in reducing poverty by one-half, creating almost 13 million jobs, halving the country's debt burden, raising foreign exchange reserves to a comfortable position and propping the country's exchange rate, restoring investors' confidence and most importantly, taking Pakistan out of the IMF Program.

The above facts were acknowledged by the last PPP government in a Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies (MEFP) for 2008/09-2009/10, while signing agreement with the IMF on November 20, 2008. The document clearly (but grudgingly) acknowledged that "Pakistan's economy witnessed a major economic transformation in the last decade. The country's real GDP increased from $60 billion to $170 billion, with per capita income rising from under $500 to over $1000 during 2000-07". It further acknowledged that "the volume of international trade increased from $20 billion to nearly $60 billion. The improved macroeconomic performance enabled Pakistan to re-enter the international capital markets in the mid-2000s. Large capital inflows financed the current account deficit and contributed to an increase in gross official reserves to $14.3 billion at end-June 2007. Buoyant output growth, low inflation, and the government's social policies contributed to a reduction in poverty and improvement in many social indicators". (see MEFP, November 20, 2008, Para 1)

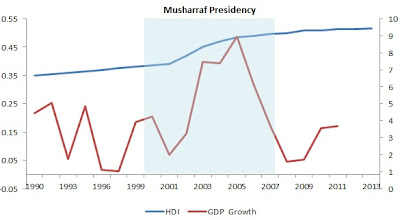

In addition to faster economic growth, Pakistan's human development index (HDI) also grew at an average rate of 2.7% per year under President Musharraf from 2000 to 2007, and then its pace slowed to 0.7% per year in 2008 to 2012 under elected politicians, according to the 2013 Human Development Report titled The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. Overall, Pakistan's human development score rose by 18.9% during Musharraf years and increased just 3.4% under elected leadership since 2008. The news on the human development front got even worse in the last three years, with HDI growth slowing down as low as 0.59% a paltry average annual increase of under 0.20 per cent.

Going further back to the decade of 1990s when the civilian leadership of the country alternated between PML (N) and PPP, the increase in Pakistan's HDI was 9.3% from 1990 to 2000, less than half of the HDI gain of 18.9% on Musharraf's watch from 2000 to 2007.

Acceleration of HDI growth during Musharraf years was not an accident. Not only did Musharraf's policies accelerate economic growth, helped create 13 million new jobs, cut poverty in half and halved the country's total debt burden in the period from 2000 to 2007, his government also ensured significantinvestment and focus on education and health care. In 2011, a Pakistani government commission on educationfound that public funding for education has been cut from 2.5% of GDP in 2007 to just 1.5% - less than the annual subsidy given to the various PSUs including Pakistan Steel and PIA, both of which continue to sustain huge losses due to patronage-based hiring.

Why is it that the military rulers have consistently delivered better economic and social results while the politicians have not been able to mach them? To put it all in perspective, let's recall how late Dr. Mahbub ul-Haq, the renowned Pakistani economist who is credited with the idea of UNDP's human development index (HDI), explained the corrosive impact of political patronage on economic policy in Pakistan.

In a 10/12/1988 interview with Professor Anatol Lieven of King's College and quoted in a recent book "Pakistan-A Hard Country", here is what Dr. Haq said:

Discussing the politics of patronage in Pakistan, Professor Lieven, the author of"Pakistan-A Hard Country", sees a silver lining to it by describing the difference between Nigeria and Pakistan in the following words:

Having just voted and elected new leaders in general elections on May 11, it is important that the voters demand an explanation from the new leadership for their extremely poor performance in the social sector in the past. Without accountability, these politicians will continue to ignore the badly needed investments required to develop the nation's human resources for a better tomorrow. Forcing the political leaders to prioritize social sector development is the best way to launch Pakistan on a faster trajectory.

Here's a video discussion on the subject recorded on Pakistan's independence day:

http://www.riazhaq.com/2013/05/looking-back-at-military-rule-in.html

"Mr. Suhartos spirit continues to loom over modern-day Indonesia. He brought the country back from the brink of political, social and economic calamity in the mid-1960s,dramatically reduced poverty and by the early 1990s had turned Indonesia into one of the Asian tiger economies. But he also governed with an iron fist, sending his jackbooted military into separatist-minded regions, jailing and exiling political enemies, quashing democratic institutions and the news media, and presiding over what some claim is one of the most corrupt governments in modern history.....Tuesday is the 15th anniversary of Mr. Suhartos resignation as president. .... Since then, Indonesia has undergone a dramatic transformation toward democracy and now has open elections and the worlds 16th-largest economy. Yet corruption remains endemic, crime is higher than during Mr. Suhartos New Order regime, and Jakarta and other large cities have chronic traffic problems".

Both Indonesia and Pakistan have each seen about 30 years of military rule. So why has Indonesia become an Asian tiger economy and Pakistan has not?

One possible explanation is that while there was 32 years uninterrupted military rule with sustained development in Indonesia, Pakistan has seen three stints of high growth under military generals in 1960s, 1980s and 2000s separated by three periods of slow or very slow growth under civilian rule in 1950s, 1970s and 1990s. Pakistani military rulers have also been less ruthless and more benevolent than Gen Suharto.

Pakistan has also experienced economic andsocial progress comparable to Indonesia's during periods of military rule. There has been much better governance and significantly faster rates of economic and social development during military rule than under civilian leaders. Many economists persuasively argue that Pakistan would have developed as fast as South Korea had the Ayub era policies continued uninterrupted for another decade or two.

Pakistan's first military dictator General Ayub Khan's period is labeled by Pakistani economist Dr. Ishrat Husain as "the Golden Sixties". General Ayub Khan pushed central planning with a state-driven national industrial policy. Countries like Malaysia and South Korea saw Pakistan as a model for export-led growth, according to Prof Stephen Cohen. In fact, South Korea sought to emulate Pakistan's development strategy and copied Pakistan's second "Five-Year Plan".

Here's how Dr. Husain recalls Pakistan of 1960s:

"The manufacturing sector expanded by 9 percent annually and various new industries were set up. Agriculture grew at a respectable rate of 4 percent with the introduction of Green Revolution technology. Governance improved with a major expansion in the governments capacity for policy analysis, design and implementation, as well as the far-reaching process of institution building. The Pakistani polity evolved from what political scientists called a soft state to a developmental one that had acquired the semblance of political legitimacy. By 1969, Pakistans manufactured exports were higher than the exports of Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia combined. Though speculative, it is possible that, had the economic policies and programs of the Ayub regime continued over the next two decades, Pakistan would have emerged as another miracle economy."

Pakistanis have found that each time a military ruler has been forced out and replaced by a civilian government led by politicians, both the economic and the social indicators have suffered. For example, Pakistan's decade of 1990s under the PPP and the PML rule is remember by economists as the lost decade. It was followed by a rebound of robust social and economic development during the Musharraf period from year 2000 to 2007.

In the 1990s, economic growth plummeted to between 3% and 4%, poverty rose to 33%, inflation was in double digits and the foreign debt mounted to nearly the entire GDP of Pakistan as the governments of Benazir Bhutto (PPP) and Nawaz Sharif (PML) played musical chairs. Before Sharif was ousted in 1999, the two parties had presided over a decade of corruption and mismanagement. In 1999 Pakistans total public debt as percentage of GDP was the highest in South Asia 99.3 percent of its GDP and 629 percent of its revenue receipts, compared to Sri Lanka (91.1% & 528.3% respectively in 1998) and India (47.2% & 384.9% respectively in 1998). Internal Debt of Pakistan in 1999 was 45.6 per cent of GDP and 289.1 per cent of its revenue receipts, as compared to Sri Lanka (45.7% & 264.8% respectively in 1998) and India (44.0% & 358.4% respectively in 1998).

The year 1999 brought a bloodless coup led by General Pervez Musharraf, ushering in an era of accelerated economic growth that led to more than doubling of the national GDP, and dramatic expansion in Pakistan's urban middle class. Pakistan became one of the four fastest growing economies in the Asian region during 2000-07 with its growth averaging 7.0 per cent per year for most of this period. As a result of strong economic growth, Pakistan succeeded in reducing poverty by one-half, creating almost 13 million jobs, halving the country's debt burden, raising foreign exchange reserves to a comfortable position and propping the country's exchange rate, restoring investors' confidence and most importantly, taking Pakistan out of the IMF Program.

The above facts were acknowledged by the last PPP government in a Memorandum of Economic and Financial Policies (MEFP) for 2008/09-2009/10, while signing agreement with the IMF on November 20, 2008. The document clearly (but grudgingly) acknowledged that "Pakistan's economy witnessed a major economic transformation in the last decade. The country's real GDP increased from $60 billion to $170 billion, with per capita income rising from under $500 to over $1000 during 2000-07". It further acknowledged that "the volume of international trade increased from $20 billion to nearly $60 billion. The improved macroeconomic performance enabled Pakistan to re-enter the international capital markets in the mid-2000s. Large capital inflows financed the current account deficit and contributed to an increase in gross official reserves to $14.3 billion at end-June 2007. Buoyant output growth, low inflation, and the government's social policies contributed to a reduction in poverty and improvement in many social indicators". (see MEFP, November 20, 2008, Para 1)

In addition to faster economic growth, Pakistan's human development index (HDI) also grew at an average rate of 2.7% per year under President Musharraf from 2000 to 2007, and then its pace slowed to 0.7% per year in 2008 to 2012 under elected politicians, according to the 2013 Human Development Report titled The Rise of the South: Human Progress in a Diverse World. Overall, Pakistan's human development score rose by 18.9% during Musharraf years and increased just 3.4% under elected leadership since 2008. The news on the human development front got even worse in the last three years, with HDI growth slowing down as low as 0.59% a paltry average annual increase of under 0.20 per cent.

Going further back to the decade of 1990s when the civilian leadership of the country alternated between PML (N) and PPP, the increase in Pakistan's HDI was 9.3% from 1990 to 2000, less than half of the HDI gain of 18.9% on Musharraf's watch from 2000 to 2007.

Acceleration of HDI growth during Musharraf years was not an accident. Not only did Musharraf's policies accelerate economic growth, helped create 13 million new jobs, cut poverty in half and halved the country's total debt burden in the period from 2000 to 2007, his government also ensured significantinvestment and focus on education and health care. In 2011, a Pakistani government commission on educationfound that public funding for education has been cut from 2.5% of GDP in 2007 to just 1.5% - less than the annual subsidy given to the various PSUs including Pakistan Steel and PIA, both of which continue to sustain huge losses due to patronage-based hiring.

Why is it that the military rulers have consistently delivered better economic and social results while the politicians have not been able to mach them? To put it all in perspective, let's recall how late Dr. Mahbub ul-Haq, the renowned Pakistani economist who is credited with the idea of UNDP's human development index (HDI), explained the corrosive impact of political patronage on economic policy in Pakistan.

In a 10/12/1988 interview with Professor Anatol Lieven of King's College and quoted in a recent book "Pakistan-A Hard Country", here is what Dr. Haq said:

"Growth in Pakistan has never translated into budgetary security because of the way our political system works. We could be collecting twice as much in revenue - even India collects 50% more than we do - and spending the money on infrastructure and education. But agriculture in Pakistan pays no tax because the landed gentry controls politics and therefore has a grip on every government. Businessman are given state loans and then allowed to default on them in return for favors to politicians and parties. Politicians protect corrupt officials so they can both share the proceeds.

And every time a new political government comes in they have to distribute huge amounts of state money and jobs as rewards to politicians who have supported them, and short term populist measures to try to convince the people that their election promises meant something, which leaves nothing for long-term development. As far as development is concerned, our system has all the worst features of oligarchy and democracy put together.

That is why only technocratic, non-political governments in Pakistan have ever been able to increase revenues. But they can not stay in power for long because they have no political support...For the same reason we have not been able to deregulate the economy as much as I wanted, despite seven years of trying, because the politicians and officials both like the system Bhutto (Late Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto) put in place. It suits them both very well, because it gave them lots of lucrative state-sponsored jobs in industry and banking to take for themselves or distribute to their relatives and supporters."

To summarize, there is insufficient revenue collected by the state of Pakistan, and the diversion of this very limited revenue to political patronage fosters dependence on foreign aid and impinges on the nation's sovereignty. It also seriously harms Pakistan's ability to invest in education, health care and infrastructure development in terms of school and hospital buildings, roads, rails, and water and energy projects for Pakistan's future.And every time a new political government comes in they have to distribute huge amounts of state money and jobs as rewards to politicians who have supported them, and short term populist measures to try to convince the people that their election promises meant something, which leaves nothing for long-term development. As far as development is concerned, our system has all the worst features of oligarchy and democracy put together.

That is why only technocratic, non-political governments in Pakistan have ever been able to increase revenues. But they can not stay in power for long because they have no political support...For the same reason we have not been able to deregulate the economy as much as I wanted, despite seven years of trying, because the politicians and officials both like the system Bhutto (Late Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto) put in place. It suits them both very well, because it gave them lots of lucrative state-sponsored jobs in industry and banking to take for themselves or distribute to their relatives and supporters."

Discussing the politics of patronage in Pakistan, Professor Lieven, the author of"Pakistan-A Hard Country", sees a silver lining to it by describing the difference between Nigeria and Pakistan in the following words:

"Rather than being eaten by a pride of lions, or even torn apart by a flock of vultures, the fate of Pakistan's national resources more closely resembles being nibbled away by a horde of mice (and the occasional large rat). The effect on the resources, and on the state's ability to do things, are just the same, but more of the results are plowed back into the society, rather than making their way straight to bank accounts in the West. This is an important difference between Pakistan and Nigeria, for example."

I personally see no better explanation for the boom under President Musharraf in 2000-2007, followed by current economic crisis since 2008, than the prevailing system of political patronage continuing to trump good public policy almost 23 years after late Dr. Mehboob ul Haq described it so well.Having just voted and elected new leaders in general elections on May 11, it is important that the voters demand an explanation from the new leadership for their extremely poor performance in the social sector in the past. Without accountability, these politicians will continue to ignore the badly needed investments required to develop the nation's human resources for a better tomorrow. Forcing the political leaders to prioritize social sector development is the best way to launch Pakistan on a faster trajectory.

Here's a video discussion on the subject recorded on Pakistan's independence day:

http://www.riazhaq.com/2013/05/looking-back-at-military-rule-in.html