Can, #religion, #caste be banned from #India's politics? #BJP #congressparty #Modi #Hindu #Sikh #Dalit #Muslim

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/op...preme-court-ban-politics-170127131816254.html

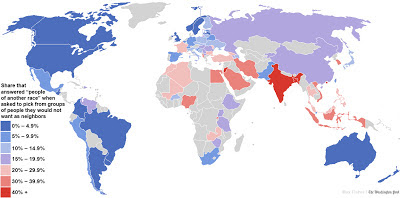

India is a nation of caste and religion. It is a nation where caste is policy. Upper caste policy is to move upwards, while lower castes continually struggle in their lowly status.

Everything that happens here is based on caste. At every stage of our life caste becomes important. We are unable to understand what is going on in the country if we disregard caste. We also see Justice T S Thakur, who delivered the court ruling, through the eyes of caste because the surname, Thakur, also represents a caste.

When caste is so integral in our society how can we separate caste and religion - a solid foundation - from politics and elections?

There are three main parties in India today: the Congress Party, the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the Communist Party. The Congress and BJP are outwardly "secular" parties. The BJP promotes itself as the party for Hindus, and on caste issues it says it is "secular". However they choose to self-define, if we search further, we find that the soul of these parties is brahminical, i.e. belonging to the highest caste.

The prominence of caste also applies to politics before India's independence. Priestly Brahmins who controlled the Bania caste - which had close business connections with them - have unjustly benefited from the new political reality, and that is why India's politics is called Brahmin-Bania politics.

-----------

In the first days of this year, in a landmark ruling, the Supreme Court of India banned political candidates from seeking election on the basis of caste, religion and language. On the surface, this ruling seems to be appealing to secular voters, upholding the secular values of the constitution and implementing the principles of democracy.

But it also seems to be contradicting a 1995 Supreme Court ruling which considered "Hindutva" (Hindu nationalism) and "Hinduism" a "way of life", rather than an ideology that belongs to a certain caste or religion. The court has been silent on reviewing the Hindutva issue.

There has been praise from seculars on the ruling and respect for the judiciary has further increased among ordinary people. But while the verdict is indeed an important new development, there are still questions about its practicality because caste, like religion, remains an integral part of Indian society.

Edit Post

Edit Post