By Malik Siraj Akbar

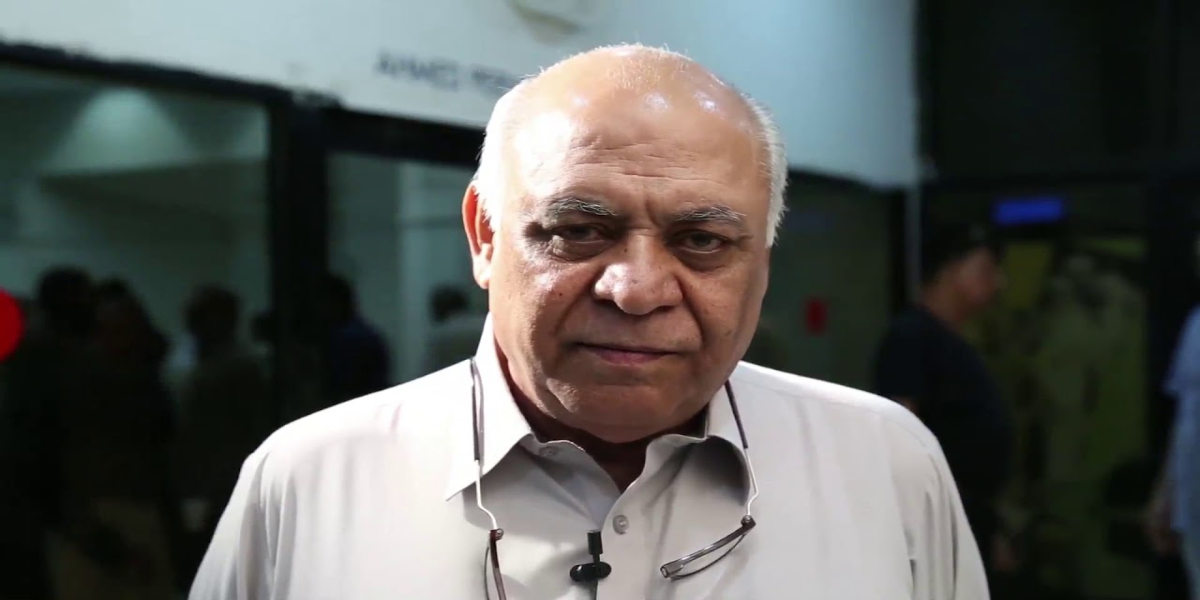

If you are a Baluch politician, activist, or a writer who gets generous praise from Islamabad, you must be doing something wrong for your people. The legacy of the late Senator Hasil Bizenjo, 62, head of the National Party who passed away on August 20 in Karachi, can also be defined by how valuable the Pakistani military, politicians, and the mainstream national media describe him. Since the president, the prime minister, or the army chief did not travel to Baluchistan to attend Bizenjo’s funeral, it is safe to assume that he was not an ‘asset’ for Islamabad. He has been widely eulogized for his commitment to democracy, nonviolence, and support for Pakistan’s Constitution. That does not necessarily mean that principles that made him amiable in Islamabad also made him a role model among all segments of the Baloch nationalist movement.

Bizenjo’s politics appealed to a particular age group. This was mainly people of his generation who entered politics after the passage of the 1973 Constitution. The Constitution was (is) not perfect. Still, this segment of politicians, that identified as progressive and nationalists, devoted the rest of their lives hoping to improve the Constitution by aligning it with the needs of smaller provinces. Bizenjo’s generation had enormous faith that someday the Constitution would be modified or adjusted to protect the rights and the interests of everyone in Pakistan, particularly that of the smaller provinces.

Bizenjo found himself in a dual dilemma. One, no matter how high he rose on the political stage (from becoming a federal minister to a senator), he could not come out of the shadow of his father, the late Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo. He was always known, identified and referenced as Bizenjo’s son. He was certainly proud of his father’s politics and he wholeheartedly followed his political philosophy. The disadvantage of this approach was that his politics never evolved with the time given Baluchistan’s changing and challenging political landscape. When his father passed away in 1989, Pakistan had freshly come out of General Zia-ul-Haq’s decade-long dictatorship and the dawn of a new democratic era awaited Pakistan. Hence, the junior Bizenjo thrived and made a name for himself in the 1990s. That was a rare decade of peace and stability in Baluchistan.

Bizenjo’s politics had prepared him to fight for Baluchistan’s rights for the decade in which the PPP and the PML- shared two terms each. However, that set of political expertise began to dwindle and become irrelevant as General Musharraf ignited the flames of a miscalculated and deeply flammable policy in Baluchistan. As tensions between the Pakistani military and the Baluch insurgents escalated, the separatist narrative gained momentum.

Bizenjo’s politics soon inevitably ended up clashing with that of the new generation of the Baluch nationalists who had not only become more radical in their demands (asking for independence rather than autonomy). This triggered a fresh race as to who was an actual Baluch nationalist; who actually represented the Baluch interests; what the Baluch actually want and how they should proceed toward achieving their rights. Not only was this new generation more revolutionary in its demands, but it was also intolerant and brutally violent [toward those who disagreed with them]. Anyone who did not agree with their political philosophy, strategy or methods was treated as a ‘traitor’ or a ‘collaborator’.

In the fight between the two extremes (the Pakistani security establishment versus several Baluch armed groups), Bizenjo’s National Party became an easy target of the Baluch armed groups. Not much is discussed about this ‘civil war’ within Baluchistan but this consumed much of Bizenjo’s time and accounted for a bulk of his talking points. Threats from the Baluch armed groups against the National Party became so severe that a grassroots politician like Bizenjo had to think of his safety before traveling inside Baluchistan.

He spent a lot of time arguing why the call for an independent Baluchistan was adventurous and unrealistic.

Bizenjo became somewhat irrelevant in Baluchistan’s current turmoil because he failed to convince the new generation of the Baluch nationalists that the 1970 Constitution can address all their needs and demands and they must give up the armed struggle. He also failed to convince the Pakistani establishment that he had enough political and social capital that he could employ to disarm the armed groups and end the insurgency in the province. He could not persuade anyone influential in Islamabad, from Nawaz Sharif to Imran Khan, that the use of guns and violence by the State should stop as it would only backfire.

Bizenjo was often underestimated when compared to his father. Let’s not forget that he lived amid harder and more dangerous political and security challenges than his father. The political polarization, rampant violence and the widespread presence of insurgent groups and government-backed anti-nationalist death squads were not what Hasil’s father had to deal with in the 1970s. The junior Bizenjo was a brave politician. He did not mince words. He was not a blind “patriotic Pakistani” like the leaders of the Baluchistan Awami Party. He, at the same time, had the courage to tell the Baluch separatists to their face that he disagreed with their politics and approach.

In an interview for the Friday Times soon after Nawab Bugti’s killing in 2006, he told me the idea of “Independent Baluchistan is nonsense.” Bizenjo, until his death, believed that the armed struggle for the attainment of the Baluch rights was a flawed approach, and the confrontation with Islamabad would backfire against the Baluch. In the same interview, I asked him if he concurred with those Baluch nationalists who believe that the parliament does not solve Baluchistan’s problems. He said, “As democratic forces, we need to continue our democratic struggle. What does it mean to quit the parliament? Where else can we raise our voice if not in the assemblies? I think we don’t need to act in frustration. Politics requires strong nerves to face hard times. I am convinced that we need to sit in the assemblies to continue our struggle.”

Bizenjo’s death marks the departure of yet another critical leader of the Baluch nationalist movement who dominated the political arena for three decades but fell inadequate to successfully fight and win Baluchistan’s case in/against Islamabad.

In 1989, when Hasil’s father died, so many young activists (such as the former chief minister Dr. Malik Baluch, and others) wanted to follow his footsteps and become someone like him. The BBC recently reported about the middle-class Pakistani [Baluch] students fighting for a homeland dream. In the backdrop of a persistent tide of support for separatist groups among educated young Baluch students, the question that can best help us capture Bizenjo’s impact on Baluchistan’s politics and his legacy is this: Do young people in Baluchistan today want to be like Hasil Bizenjo the way an earlier generation wanted to be like Ghaus Bakhsh Bizenjo?

Malik Siraj Akbar is the editor-in-chief of the Baluch Hal

Email: [email protected]

The Legacy of Hasil Bizenjo (1958-2020)

By Malik Siraj Akbar If you are a Baluch politician, activist, or a writer who gets generous praise from Islamabad, you must be doing something wrong for your people. The legacy of the late Se…

thebaluchhal.com

thebaluchhal.com