The book being reviewed was Rise and Kill First by New York Times reporter Ronen Bergman, a weighty study of the Mossad, Israel’s foreign intelligence service, together with its sister agencies.

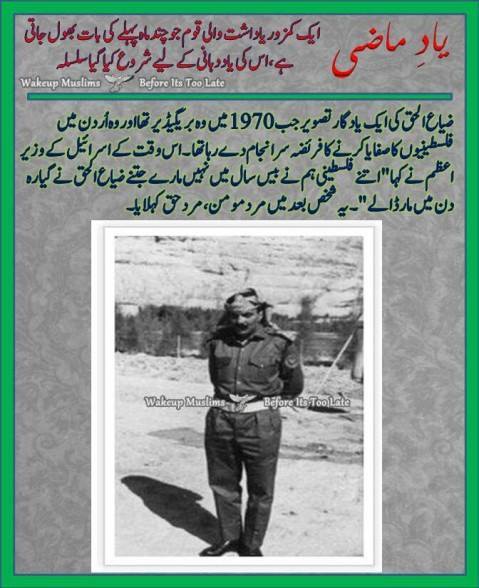

The author devoted six years of research to the project, which was based upon a thousand personal interviews and access to an enormous number of official documents previously unavailable. As suggested by the title, his primary focus was Israel’s long history of assassinations, and across his 750 pages and thousand-odd source references he recounts the details of an enormous number of such incidents.

That sort of topic is obviously fraught with controversy, but Bergman’s volume carries glowing cover-blurbs from Pulitzer Prize-winning authors on espionage matters, and the official cooperation he received is indicated by similar endorsements from both a former Mossad chief and Ehud Barak, a past Prime Minister of Israel who himself had once led assassination squads.

Over the last couple of decades, former CIA officer Robert Baer has become one of our most prominent authors in this same field, and he praises the book as “hands down” the best he has ever read on intelligence, Israel, or the Middle East. The reviews across our elite media were equally laudatory.

Although I had seen some discussions of the book when it appeared, I only got around to reading it a few months ago. And while I was deeply impressed by the thorough and meticulous journalism, I found the pages rather grim and depressing reading, with their endless accounts of Israeli agents killing their real or perceived enemies in operations that sometimes involved kidnappings and brutal torture, or resulted in considerable loss of life to innocent bystanders.

Although the overwhelming majority of the attacks described took place in the various countries of the Middle East or the occupied Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza, others ranged across the world, including Europe. The narrative history began in the 1920s, decades before the actual creation of the Jewish Israel or its Mossad organization, and extended down to the present day.

The sheer quantity of such foreign assassinations was really quite remarkable, with the knowledgeable reviewer in the New York Times suggesting that the Israeli total over the last half-century or so seemed far greater than that of any other nation. I might even go farther: if we excluded domestic killings, I wouldn’t be surprised if the body-count exceeded the combined total for that of all other major countries in the world.

I think all the lurid revelations of lethal CIA or KGB Cold War assassination plots that I have seen discussed in newspaper articles might fit comfortably into just a chapter or two of Bergman’s extremely long book.

National militaries have always been nervous about deploying biological weapons, knowing full well that once released, the deadly microbes might easily spread back across the border and inflict great suffering upon the civilians of the country that deployed them.

Similarly, intelligence operatives who have spent their long careers so heavily focused upon planning, organizing, and implementing what amount to officially-sanctioned murders may develop ways of thinking that become a danger both to each other and to the larger society they serve, and some examples of this possibility leak out here and there in Bergman’s comprehensive narrative.

In the so-called “Askelon Incident” of 1984, a couple of captured Palestinians were beaten to death in public by the notoriously ruthless head of the Shin Bet domestic security agency and his subordinates. Under normal circumstances, this deed would have carried no consequences, but the incident happened to be captured by the camera by a nearby Israeli photo-journalist, who managed to avoid confiscation of his film.

His resulting scoop sparked an international media scandal, even reaching the pages of the New York Times, and this forced a governmental investigation aimed at criminal prosecution. To protect themselves, the Shin Bet leadership infiltrated the inquiry and organized an effort to fabricate evidence pinning the murders upon ordinary Israeli soldiers and a leading general, all of whom were completely innocent.

A senior Shin Bet officer who expressed misgivings about this plot apparently came close to being murdered by his colleagues until he agreed to falsify his official testimony. Organizations that increasingly operate like mafia crime families may eventually adopt similar cultural norms.

Israeli operatives sometimes even contemplated the elimination of their own top-ranking leaders whose policies they viewed as sufficiently counter-productive.

For decades, Gen. Ariel Sharon had been one of Israel’s greatest military heroes and someone of extreme right-wing sentiments. As Defense Minister in 1982, he orchestrated the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, which soon turned into a major political debacle, seriously damaging Israel’s international standing by inflicting great destruction upon that neighboring country and its capital city of Beirut.

As Sharon stubbornly continued his military strategy and the problems grew more severe, a group of disgruntled officers decided that the best means of cutting Israel’s losses was to assassinate Sharon, though the proposal was never carried out.

An even more striking example occurred a decade later. For many years, Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat had been the leading object of Israeli antipathy, so much so that at one point Israel made plans to shoot down an international civilian jetliner in order to assassinate him.

But after the end of the Cold War, pressure from America and Europe led Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin to sign the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords with his Palestinian foe.

Although the Israeli leader received worldwide praise and shared a Nobel Peace Prize for his peacemaking efforts, powerful segments of the Israeli public and its political class regarded the act as a betrayal, with some extreme nationalists and religious zealots demanding that he be killed for his treason.

A couple of years later, he was indeed shot dead by a lone gunman from those ideological circles, becoming the first Middle Eastern leader in decades to suffer that fate.

Although his killer was mentally unbalanced and stubbornly insisted that he acted alone, he had had a long history of intelligence associations, and Bergman delicately notes that the gunman slipped past Rabin’s numerous bodyguards “with astonishing ease” in order to fire his three fatal shots at close range.

Many observers drew parallels between Rabin’s assassination and that of our own president in Dallas three decades earlier, and the latter’s heir and namesake, John F. Kennedy, Jr., developed a strong personal interest in the tragic event. In March 1997, his glossy political magazine George published an article by the Israeli assassin’s mother, implicating her own country’s security services in the crime, a theory also promoted by the late Israeli-Canadian writer Barry Chamish.

These accusations sparked a furious international debate, but after Kennedy himself died in an unusual plane crash a couple of years later and his magazine quickly folded, the controversy soon subsided. The George archives are not online nor easily available, so I cannot easily judge the credibility of the charges.

Having himself narrowly avoided assassination by Israeli operatives, Sharon gradually regained his political influence, and did so without compromising his hard-line views, even boastfully describing himself as a “Judeo-Nazi” to an appalled journalist. A few years after Rabin’s death, he provoked major Palestinian protests, then used the resulting violence to win election as Prime Minister, while once in office, his very harsh methods led to a widespread uprising in Occupied Palestine. But Sharon merely redoubled his repression, and after world attention was diverted by 9/11 attacks and the American invasion of Iraq, he began assassinating numerous top Palestinian political and religious leaders in attacks that sometimes inflicted heavy civilian casualties.

The central object of Sharon’s anger was Palestine President Yasir Arafat, who suddenly took ill and died, thereby joining his erstwhile negotiating partner Rabin in permanent repose. Arafat’s wife claimed that he had been poisoned and produced some medical evidence to support this charge, while longtime Israeli political figure Uri Avnery published numerous articles substantiating those accusations. Bergman simply reports the categorical Israeli denials while noting that “the timing of Arafat’s death was quite peculiar,” then emphasizes that even if he knew the truth, he couldn’t publish it since his entire book was written under strict Israeli censorship.

This last point seems an extremely important one, and although it only appears just that one time in the body of the text, the disclaimer obviously applies to the entirety of the long volume and should always be kept in the back of our minds. Bergman’s book runs some 350,000 words and even if every single sentence were written with the most scrupulous honesty, we must recognize the huge difference between “the Truth” and “the Whole Truth.”

Another item also raised my suspicions. Thirty years ago, a disaffected Mossad officer named Victor Ostrovsky left that organization and wrote By Way of Deception, a highly critical book recounting numerous alleged operations known to him, especially those contrary to American and Western interests.

The Israeli government and its pro-Israel advocates launched an unprecedented legal campaign to block publication, but this produced a major backlash and media uproar, with the heavy publicity landing it as #1 on the New York Times sales list. I finally got around to reading his book about a decade ago and was shocked by many of the remarkable claims, while being reliably informed that CIA personnel had judged his material as probably accurate when they reviewed it.

Although much of Ostrovsky’s information was impossible to independently confirm, for more than a quarter-century his international bestseller and its 1994 sequel The Other Side of Deception have heavily shaped our understanding of Mossad and its activities, so I naturally expected to see a detailed discussion, whether supportive or critical, in Bergman’s exhaustive parallel work. Instead, there was only a single reference to Ostrovsky buried in a footnote on p. 684.

There we are told of Mossad’s utter horror at the numerous deep secrets that Ostrovsky was preparing to reveal, which led its top leadership to formulate a plan to assassinate him. Ostrovsky only survived because Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who had formerly spent decades as the Mossad assassination chief, vetoed the proposal on the grounds that “We don’t kill Jews.” Although this reference is brief and almost hidden, I regard it as providing considerable support for Ostrovsky’s general credibility.

Having thus acquired serious doubts about the completeness of Bergman’s seemingly comprehensive narrative history, I noted a curious fact. I have no specialized expertise in intelligence operations in general nor those of Mossad in particular, so I found it quite remarkable that the overwhelming majority of all the higher-profile incidents recounted by Bergman were already familiar to me merely from the decades I had spent closely reading the New York Times every morning. Is it really plausible that six years of exhaustive research and so many personal interviews would have uncovered so few major operations that had not already been known and reported in the international media? Bergman obviously provides a wealth of detail previously limited to insiders, along with numerous unreported assassinations of relatively minor individuals, but it seems strange that he came up with so few surprising revelations.

Indeed, some major gaps in his coverage are quite apparent to anyone who has even somewhat investigated the topic, and these begin in the early chapters of his volume, which include coverage of the Zionist prehistory in Palestine prior to the establishment of the Jewish state.

Bergman would have severely damaged his credibility if he had failed to include the infamous 1940s Zionist assassinations of Britain’s Lord Moyne or U.N. Peace Negotiator Count Folke Bernadotte. But he unaccountably fails to mention that in 1937 the more right-wing Zionist faction whose political heirs have dominated Israel in recent decades assassinated Chaim Arlosoroff, the highest-ranking Zionist figure in Palestine.

Moreover, he omits a number of similar incidents, including some of those targeting top Western leaders. As I wrote last year:

As far as I know, the early Zionists had a record of political terrorism almost unmatched in world history, and in 1974 Prime Minister Menachem Begin once even boasted to a television interviewer of having been the founding father of terrorism across the world.

In the aftermath of World War II, Zionists were bitterly hostile towards all Germans, and Bergman describes the campaign of kidnappings and murders they soon unleashed, both in parts of Europe and in Palestine, which claimed as many as two hundred lives.

A small ethnic German community had lived peacefully in the Holy Land for many generations, but after some of its leading figures were killed, the rest permanently fled the country, and their abandoned property was seized by Zionist organizations, a pattern which would soon be replicated on a vastly larger scale with regard to the Palestinian Arabs.

These facts were new to me, and Bergman seemingly treats this wave of vengeance-killings with considerable sympathy, noting that many of the victims had actively supported the German war effort. But oddly enough, he fails to mention that throughout the 1930s, the main Zionist movement had itself maintained a strong economic partnership with Hitler’s Germany, whose financial support was crucial to the establishment of the Jewish state.

Moreover, after the war began a small right-wing Zionist faction led by a future prime minister of Israel attempted to enlist in the Axis military alliance, offering to undertake a campaign of espionage and terrorism against the British military in support of the Nazi war effort.

These undeniable historical facts have obviously been a source of immense embarrassment to Zionist partisans, and over the last few decades they have done their utmost to expunge them from public awareness, so as a native-born Israeli now in his mid-40s, Bergman may simply be unaware of this reality.

Excerpts from Bergman s book.

Published in UNZ.

The author devoted six years of research to the project, which was based upon a thousand personal interviews and access to an enormous number of official documents previously unavailable. As suggested by the title, his primary focus was Israel’s long history of assassinations, and across his 750 pages and thousand-odd source references he recounts the details of an enormous number of such incidents.

That sort of topic is obviously fraught with controversy, but Bergman’s volume carries glowing cover-blurbs from Pulitzer Prize-winning authors on espionage matters, and the official cooperation he received is indicated by similar endorsements from both a former Mossad chief and Ehud Barak, a past Prime Minister of Israel who himself had once led assassination squads.

Over the last couple of decades, former CIA officer Robert Baer has become one of our most prominent authors in this same field, and he praises the book as “hands down” the best he has ever read on intelligence, Israel, or the Middle East. The reviews across our elite media were equally laudatory.

Although I had seen some discussions of the book when it appeared, I only got around to reading it a few months ago. And while I was deeply impressed by the thorough and meticulous journalism, I found the pages rather grim and depressing reading, with their endless accounts of Israeli agents killing their real or perceived enemies in operations that sometimes involved kidnappings and brutal torture, or resulted in considerable loss of life to innocent bystanders.

Although the overwhelming majority of the attacks described took place in the various countries of the Middle East or the occupied Palestinian territories of the West Bank and Gaza, others ranged across the world, including Europe. The narrative history began in the 1920s, decades before the actual creation of the Jewish Israel or its Mossad organization, and extended down to the present day.

The sheer quantity of such foreign assassinations was really quite remarkable, with the knowledgeable reviewer in the New York Times suggesting that the Israeli total over the last half-century or so seemed far greater than that of any other nation. I might even go farther: if we excluded domestic killings, I wouldn’t be surprised if the body-count exceeded the combined total for that of all other major countries in the world.

I think all the lurid revelations of lethal CIA or KGB Cold War assassination plots that I have seen discussed in newspaper articles might fit comfortably into just a chapter or two of Bergman’s extremely long book.

National militaries have always been nervous about deploying biological weapons, knowing full well that once released, the deadly microbes might easily spread back across the border and inflict great suffering upon the civilians of the country that deployed them.

Similarly, intelligence operatives who have spent their long careers so heavily focused upon planning, organizing, and implementing what amount to officially-sanctioned murders may develop ways of thinking that become a danger both to each other and to the larger society they serve, and some examples of this possibility leak out here and there in Bergman’s comprehensive narrative.

In the so-called “Askelon Incident” of 1984, a couple of captured Palestinians were beaten to death in public by the notoriously ruthless head of the Shin Bet domestic security agency and his subordinates. Under normal circumstances, this deed would have carried no consequences, but the incident happened to be captured by the camera by a nearby Israeli photo-journalist, who managed to avoid confiscation of his film.

His resulting scoop sparked an international media scandal, even reaching the pages of the New York Times, and this forced a governmental investigation aimed at criminal prosecution. To protect themselves, the Shin Bet leadership infiltrated the inquiry and organized an effort to fabricate evidence pinning the murders upon ordinary Israeli soldiers and a leading general, all of whom were completely innocent.

A senior Shin Bet officer who expressed misgivings about this plot apparently came close to being murdered by his colleagues until he agreed to falsify his official testimony. Organizations that increasingly operate like mafia crime families may eventually adopt similar cultural norms.

Israeli operatives sometimes even contemplated the elimination of their own top-ranking leaders whose policies they viewed as sufficiently counter-productive.

For decades, Gen. Ariel Sharon had been one of Israel’s greatest military heroes and someone of extreme right-wing sentiments. As Defense Minister in 1982, he orchestrated the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, which soon turned into a major political debacle, seriously damaging Israel’s international standing by inflicting great destruction upon that neighboring country and its capital city of Beirut.

As Sharon stubbornly continued his military strategy and the problems grew more severe, a group of disgruntled officers decided that the best means of cutting Israel’s losses was to assassinate Sharon, though the proposal was never carried out.

An even more striking example occurred a decade later. For many years, Palestinian leader Yasir Arafat had been the leading object of Israeli antipathy, so much so that at one point Israel made plans to shoot down an international civilian jetliner in order to assassinate him.

But after the end of the Cold War, pressure from America and Europe led Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin to sign the 1993 Oslo Peace Accords with his Palestinian foe.

Although the Israeli leader received worldwide praise and shared a Nobel Peace Prize for his peacemaking efforts, powerful segments of the Israeli public and its political class regarded the act as a betrayal, with some extreme nationalists and religious zealots demanding that he be killed for his treason.

A couple of years later, he was indeed shot dead by a lone gunman from those ideological circles, becoming the first Middle Eastern leader in decades to suffer that fate.

Although his killer was mentally unbalanced and stubbornly insisted that he acted alone, he had had a long history of intelligence associations, and Bergman delicately notes that the gunman slipped past Rabin’s numerous bodyguards “with astonishing ease” in order to fire his three fatal shots at close range.

Many observers drew parallels between Rabin’s assassination and that of our own president in Dallas three decades earlier, and the latter’s heir and namesake, John F. Kennedy, Jr., developed a strong personal interest in the tragic event. In March 1997, his glossy political magazine George published an article by the Israeli assassin’s mother, implicating her own country’s security services in the crime, a theory also promoted by the late Israeli-Canadian writer Barry Chamish.

These accusations sparked a furious international debate, but after Kennedy himself died in an unusual plane crash a couple of years later and his magazine quickly folded, the controversy soon subsided. The George archives are not online nor easily available, so I cannot easily judge the credibility of the charges.

Having himself narrowly avoided assassination by Israeli operatives, Sharon gradually regained his political influence, and did so without compromising his hard-line views, even boastfully describing himself as a “Judeo-Nazi” to an appalled journalist. A few years after Rabin’s death, he provoked major Palestinian protests, then used the resulting violence to win election as Prime Minister, while once in office, his very harsh methods led to a widespread uprising in Occupied Palestine. But Sharon merely redoubled his repression, and after world attention was diverted by 9/11 attacks and the American invasion of Iraq, he began assassinating numerous top Palestinian political and religious leaders in attacks that sometimes inflicted heavy civilian casualties.

The central object of Sharon’s anger was Palestine President Yasir Arafat, who suddenly took ill and died, thereby joining his erstwhile negotiating partner Rabin in permanent repose. Arafat’s wife claimed that he had been poisoned and produced some medical evidence to support this charge, while longtime Israeli political figure Uri Avnery published numerous articles substantiating those accusations. Bergman simply reports the categorical Israeli denials while noting that “the timing of Arafat’s death was quite peculiar,” then emphasizes that even if he knew the truth, he couldn’t publish it since his entire book was written under strict Israeli censorship.

This last point seems an extremely important one, and although it only appears just that one time in the body of the text, the disclaimer obviously applies to the entirety of the long volume and should always be kept in the back of our minds. Bergman’s book runs some 350,000 words and even if every single sentence were written with the most scrupulous honesty, we must recognize the huge difference between “the Truth” and “the Whole Truth.”

Another item also raised my suspicions. Thirty years ago, a disaffected Mossad officer named Victor Ostrovsky left that organization and wrote By Way of Deception, a highly critical book recounting numerous alleged operations known to him, especially those contrary to American and Western interests.

The Israeli government and its pro-Israel advocates launched an unprecedented legal campaign to block publication, but this produced a major backlash and media uproar, with the heavy publicity landing it as #1 on the New York Times sales list. I finally got around to reading his book about a decade ago and was shocked by many of the remarkable claims, while being reliably informed that CIA personnel had judged his material as probably accurate when they reviewed it.

Although much of Ostrovsky’s information was impossible to independently confirm, for more than a quarter-century his international bestseller and its 1994 sequel The Other Side of Deception have heavily shaped our understanding of Mossad and its activities, so I naturally expected to see a detailed discussion, whether supportive or critical, in Bergman’s exhaustive parallel work. Instead, there was only a single reference to Ostrovsky buried in a footnote on p. 684.

There we are told of Mossad’s utter horror at the numerous deep secrets that Ostrovsky was preparing to reveal, which led its top leadership to formulate a plan to assassinate him. Ostrovsky only survived because Prime Minister Yitzhak Shamir, who had formerly spent decades as the Mossad assassination chief, vetoed the proposal on the grounds that “We don’t kill Jews.” Although this reference is brief and almost hidden, I regard it as providing considerable support for Ostrovsky’s general credibility.

Having thus acquired serious doubts about the completeness of Bergman’s seemingly comprehensive narrative history, I noted a curious fact. I have no specialized expertise in intelligence operations in general nor those of Mossad in particular, so I found it quite remarkable that the overwhelming majority of all the higher-profile incidents recounted by Bergman were already familiar to me merely from the decades I had spent closely reading the New York Times every morning. Is it really plausible that six years of exhaustive research and so many personal interviews would have uncovered so few major operations that had not already been known and reported in the international media? Bergman obviously provides a wealth of detail previously limited to insiders, along with numerous unreported assassinations of relatively minor individuals, but it seems strange that he came up with so few surprising revelations.

Indeed, some major gaps in his coverage are quite apparent to anyone who has even somewhat investigated the topic, and these begin in the early chapters of his volume, which include coverage of the Zionist prehistory in Palestine prior to the establishment of the Jewish state.

Bergman would have severely damaged his credibility if he had failed to include the infamous 1940s Zionist assassinations of Britain’s Lord Moyne or U.N. Peace Negotiator Count Folke Bernadotte. But he unaccountably fails to mention that in 1937 the more right-wing Zionist faction whose political heirs have dominated Israel in recent decades assassinated Chaim Arlosoroff, the highest-ranking Zionist figure in Palestine.

Moreover, he omits a number of similar incidents, including some of those targeting top Western leaders. As I wrote last year:

As far as I know, the early Zionists had a record of political terrorism almost unmatched in world history, and in 1974 Prime Minister Menachem Begin once even boasted to a television interviewer of having been the founding father of terrorism across the world.

In the aftermath of World War II, Zionists were bitterly hostile towards all Germans, and Bergman describes the campaign of kidnappings and murders they soon unleashed, both in parts of Europe and in Palestine, which claimed as many as two hundred lives.

A small ethnic German community had lived peacefully in the Holy Land for many generations, but after some of its leading figures were killed, the rest permanently fled the country, and their abandoned property was seized by Zionist organizations, a pattern which would soon be replicated on a vastly larger scale with regard to the Palestinian Arabs.

These facts were new to me, and Bergman seemingly treats this wave of vengeance-killings with considerable sympathy, noting that many of the victims had actively supported the German war effort. But oddly enough, he fails to mention that throughout the 1930s, the main Zionist movement had itself maintained a strong economic partnership with Hitler’s Germany, whose financial support was crucial to the establishment of the Jewish state.

Moreover, after the war began a small right-wing Zionist faction led by a future prime minister of Israel attempted to enlist in the Axis military alliance, offering to undertake a campaign of espionage and terrorism against the British military in support of the Nazi war effort.

These undeniable historical facts have obviously been a source of immense embarrassment to Zionist partisans, and over the last few decades they have done their utmost to expunge them from public awareness, so as a native-born Israeli now in his mid-40s, Bergman may simply be unaware of this reality.

Excerpts from Bergman s book.

Published in UNZ.