Doctors Worry That Memory Problems After COVID-19 May Set The Stage For Alzheimer's

Medical staff members check on a patient in the COVID-19 Intensive Care Unit at United Memorial Medical Center in Houston last November. Doctors are now investigating whether people with lingering cognitive symptoms may be at risk for dementia

Before she got COVID-19, Cassandra Hernandez, 38, was in great shape — both physically and mentally.

"I'm a nurse," she says. "I work with surgeons and my memory was sharp."

Then, in June 2020, COVID-19 struck Hernandez and several others in her unit at a large hospital in San Antonio.

"I went home after working a 12-hour shift and sat down to eat a pint of ice cream with my husband and I couldn't taste it," she says.

The loss of taste and smell can be an early sign that COVID-19 is affecting a brain area that helps us sense odors.

Hernandez would go on to spend two weeks in the hospital and months at home disabled by symptoms including tremors, extreme fatigue and problems with memory and thinking.

"I would literally fall asleep if I was having a conversation or doing anything that involved my brain," she says.

Alzheimer's researchers sharing findings on COVID-19

Now, researchers at UT Health San Antonio are studying patients like Hernandez, trying to understand why their cognitive problems persist and whether their brains have been changed in ways that elevate the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease.The San Antonio researchers are among the teams of scientists from around the world who will present their findings on how COVID-19 affects the brain at the Alzheimer's Association International Conference, which begins Monday in Denver.

What scientists have found so far is concerning.

For example, PET scans taken before and after a person develops COVID-19 suggest that the infection can cause changes that overlap those seen in Alzheimer's. And genetic studies are finding that some of the same genes that increase a person's risk for getting severe COVID-19 also increase the risk of developing Alzheimer's.

Alzheimer's diagnoses also appear to be more common in patients in their 60s and 70s who have had severe COVID-19, says Dr. Gabriel de Erausquin, a professor of neurology at UT Health San Antonio. "It's downright scary," he says.

A loss of smell can signal trouble

And de Erausquin and his colleagues have noticed that mental problems seem to be more common in COVID-19 patients who lose their sense of smell, perhaps because the disease has affected a brain area called the olfactory bulb."Persistent lack of smell, it's associated with brain changes not just in the olfactory bulb but those places that are connected one way or another to the smell sense," he says.

Those places include areas involved in memory, thinking, planning and mood.

COVID-19's effects on the brain also seem to vary with age, de Erausquin says. People in their 30s seem more likely to develop anxiety and depression.

"In older people, people over 60, the foremost manifestation is forgetfulness," he says. "These folks tend to forget where they placed things, they tend to forget names, they tend to forget phone numbers. They also have trouble with language; they begin forgetting words."

The symptoms are similar to those of early Alzheimer's, and doctors sometimes describe these patients as having an Alzheimer's-like syndrome that can persist for many months.

Short Wave

How COVID-19 Affects The Brain

"Those people look really bad right now," de Erausquin says. "And the expectation is that it may behave as Alzheimer's behaves, in a progressive fashion. But the true answer is we don't know."Another scientist who will present research at the Alzheimer's conference is Dr. Sudha Seshadri, founding director of the Glenn Biggs Institute for Alzheimer's and Neurodegenerative Diseases at UT Health San Antonio.

The possibility that COVID-19 might increase the risk of Alzheimer's is alarming, Seshadri says. "Even if the effect is small, it's something we're going to have to factor in because the population is quite large," she says.

In the U.S. alone, millions of people have developed persistent cognitive or mood problems after getting COVID-19. It may take a decade to know whether these people are more likely than uninfected people to develop Alzheimer's in their 60s and 70s, Seshadri says.

Studies of people who have had COVID-19 may help scientists understand the role infections play in Alzheimer's and other brain diseases. Previous research has suggested that exposure to certain viruses, including herpes, can trigger an immune response in the brain that may set the stage for Alzheimer's.

"If one understands how the immune response to this virus is accelerating [Alzheimer's] disease, we may learn about the impact of other viruses," Seshadri says.

A long road back from COVID-19

Meanwhile, people like Cassandra Hernandez, the nurse, are simply trying to get better. More than a year after getting sick, she says, her brain is still foggy."We were at dinner and I forgot how to use a fork," she says. "It was embarrassing."

Even so, Hernandez says she's improving — slowly.

"Before this I was working on my master's," she says. "Now I can do basic math, addition and subtraction, I can read at a fifth-grade level. I'm still working hard every day."

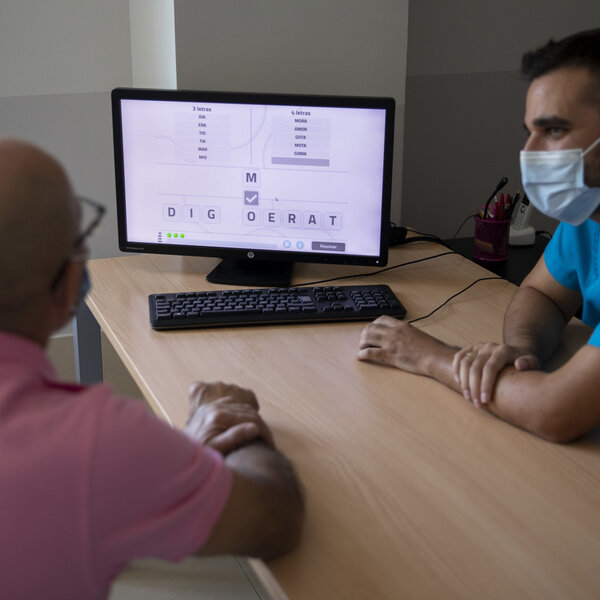

Hernandez has been working with Dr. Monica Verduzco-Gutierrez, chair of the department of physical medicine and rehabilitation at UT Health and director of the COVID-19 recovery clinic.

Verduzco-Gutierrez says her practice used to revolve around people recovering from strokes and traumatic brain injuries. Now she spends some days seeing only patients recovering from COVID-19.

The most common complaint is fatigue, Verduzco-Gutierrez says. But these patients also frequently experience migraine headaches, forgetfulness, dizziness and balance issues, she says.

Some of these patients may never recover fully, Verduzco-Gutierrez says. But she's hopeful for Hernandez.

"She's made so much improvement and I would love for her to go back to nursing," Verduzco-Gutierrez says. "But again, we don't know what happens with this disease."

Source